Spasticity

Neurological disease or injury can affect many body functions including muscles. Individuals most often affected by spasticity (tone) are those with diagnoses of spinal cord injury (SCI), stroke, brain injury, cerebral palsy and multiple sclerosis. Others with neurologic issues can develop spasticity (tone) as well.

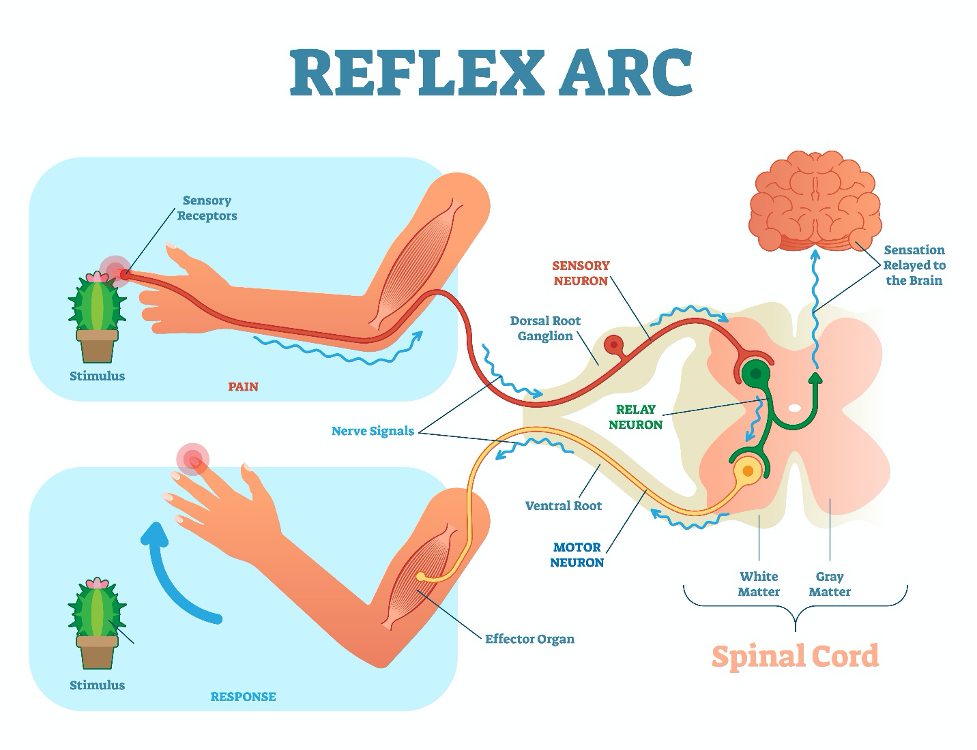

In the nervous system, sensory nerves carry messages from inside the body or from the skin to the brain. These messages indicate if there is an issue, if something good is happening or if an adjustment needs to be made. The brain analyzes this information instantly. Messages are then sent to move through a response in the motor system. When the motor system is affected by disease or injury, spasticity can occur. The message for movement is either not received or misinterpreted resulting in involuntary tightening of a muscle or groups of muscles.

If you have a sudden injury to your spinal cord or brain, the motor nerves can be affected. Spasticity can develop any time after a brain injury. Immediately after a spinal cord injury, your body below the level of injury becomes flaccid or without muscle response. Involuntary muscle movement or spasticity (tone) does not develop until typically six weeks after injury. It may start as a small twitch or develop fully quickly. Many individuals might mistake this involuntary, uncontrolled movement for voluntary function.

If you have an injury to your spinal cord or brain from a disease, spasticity (tone) will develop if the motor strip in the brain, or if the motor nerves in the brain, spinal cord or body are affected. Only the muscles that are controlled by the affected motor nerves will develop spasticity (tone). Spasticity may develop in a part of your body but not in other areas depending on which motor nerves are affected. Spasticity may gradually increase as your disease progresses or may develop quickly. Recovery from your disease might coincide with a decrease spasticity (tone).

There are different forms of spasticity and involuntary muscle contractions. People tend to lump them into the term spasticity (tone), but there are differences. These are the definitions of the terms:

A muscle spasm can happen to anyone with or without a spinal cord or brain injury. This is a random involuntary contraction of a muscle anywhere in the body. It can be a light twitch around the eye or a sudden knot in the leg. Most often muscle spasms appear in the feet, hands, arms, thighs, abdomen or in the muscles between the ribs. A spasm in the muscles between the ribs (intercostal) usually occurs after heavy physical activity such as running. Some people call it a stitch in their side.

There are many causes of muscle spasms which include fatigue, stress, under or overuse of muscles, dehydration, low potassium or low magnesium levels. Gently stretching the muscle usually resolves the issue. Resting the muscle also helps. Muscle spasms usually resolve spontaneously. They might appear as a single or a few episodes. Getting a health assessment is important if the muscle spasms become frequent.

A spasm is a single episode of involuntary muscle contraction. After spinal cord injury or brain injury, these are a result of injury to a specific section of the nervous system called the upper motor neurons.

Spasticity (tone) is an involuntary contraction of one or more muscles. Spasticity is a collective term that describes recurrent spasms.

Hypertonia is a muscle at rest that has so much spasticity that it is rigid. The muscle resists movement due to the excessive amount of spasm (tone). At times, hypertonia is so strong that the muscle cannot be manually stretched.

Spinal cord injury specialists will refer to spasticity and involuntary muscle contractions as tone. This is because of the medical word hypertonia meaning so much spasticity that the muscle is rigid. Therefore, using the word tone is a classification of intermittent uncontrolled muscle movement without rigidity or uncontrolled movement without hyperactivity. Tone is replacing the less medically oriented term, spasticity.

Clonus is a form of spasticity (tone) which has a continuous and rhythmic pattern. Most people will describe the movement as having a beat. Clonus can usually be interrupted in the leg or arm by stretching the spasming muscle.

How Spasticity (Tone) Develops–the Physiology

Spasticity (tone) develops when there is an injury in certain parts of the nervous system. These are upper motor neurons, the spinal cord reflexes and the stretch reflex of the muscle affected.

Nervous System Control of the Body Sensory nerves send messages from the body to the brain. These messages are created from information gathered by the sensory nerves of the skin and those from within the body. The sensory nerves indicate if the body is feeling pleasure, feeling distress or functioning well. Instantaneously, the brain will respond for the body to adjust by messages sent through motor neurons. Motor neurons receive messages from the brain to send to the body. The motor neurons will speed up or slow down activity inside the body as well as tell the body to move for adjustments in positioning and comfort. Motor neurons control muscles, internal organs and glands. Body functions and movement are regulated by motor neurons.

Movement is Controlled by Motor Neurons There are two types of motor neurons, upper motor neurons (UMN) and lower motor neurons (LMN). Although they share the same name, motor neurons, there are more differences than similarities. UMNs originate in the brain, specifically in the motor strip section. LMNs originate in the brainstem or spinal cord. Injury to UMNs lead to spasticity (tone).

Most typically, injuries to the cervical or thoracic levels of the spinal cord will result in changes to UMN functioning which results in spasticity (tone). Injuries at the lumbar or sacral areas result in LMN function changes which are flaccid muscles or limp muscles. This is often the case but there can also be mixed effects which are a result of a combination of symptoms of UMN (spasticity) and LMN (flaccidity) injury.

Reflexes There are four types of reflexes in the body. Two of these reflex systems are affected after SCI, brain injury and other neurological diseases that result in spasticity (tone). Control of the motor system in the body can be affected by injury to the spinal cord reflexes. You will note these reflexes are affected when a healthcare provider taps the knee with a reflex hammer. The knee jerk reflex can be absent, or the knee jerking will be prolonged which is spasticity.

The more prominent reflex leading to spasticity is actually within the muscle. Each muscle has it own muscle stretch reflex which allows it to stretch and contract with movement. Muscles require stretch/contracting movement as a typical part of their use. When muscles are not moved by functional use or by having them moved for you, the muscle stretch reflex is not activated. The muscle then becomes hyperactive within itself resulting in spasticity (tone). This is the muscles rudimentary way of seeking the muscle stretch reflex.

There are a variety of physiologic factors that affect spasticity (tone). Some are known as indicated above. There are additional physiologic factors yet to be understood.

Symptoms of Spasticity (Tone)

Onset In spinal cord injury from trauma, spasticity does not begin until about six weeks after injury. For the first six weeks, the muscles are flaccid. After six weeks, spasticity will begin. In spinal cord injury from disease, spasticity typically begins as the disease progresses affecting the nerves and muscles. For individuals diagnosed with stroke, spasticity can begin immediately after time of injury to the brain or later. For those with brain injury, spasticity most often begins about one week after injury. In other neurological diagnoses, spasticity typically develops as the disease progresses.

Symptoms of spasticity are increased muscle tone, overactive reflexes, involuntary movements, pain, tightness, recurrent spasms, and clonus. If you have decreased sensation in your body, you may not feel pain or tightness. Instead, your body may react with episodes of autonomic dysreflexia (AD), a condition where the blood pressure elevates in response to the spasticity stimulus. More information about AD can be found here.

Complications of spasticity (tone) include difficulty with activities of daily living such as decreased functional abilities and difficulty with care and hygiene. Physical changes can occur such as abnormal posture sometimes resulting in breathing difficulty, contractures (shortening) of the muscles and tendons, and bone and joint deformities. It can delay progress in recovery. Spasticity can impede development in children.

A sudden increase in spasticity (tone) or change in your spasticity pattern can be an indication of a newly developed complication. Spasticity can increase with the development of a urinary tract infection, pressure injury or other developing issues. For individuals with spinal cord injury, increased spasticity can be one of the first symptoms of an enlargement at the injury site within the spinal cord. The enlargement is a cyst of fluid called a syrinx.

Diagnosing Spasticity (Tone)

After an injury to the nervous system from trauma or a medical condition, there are often disruptions to the motor neurons and sensory neurons. Because the nervous system is so complicated, injuries to motor nerves are not always easily identified as UMN or LMN. Only a neurological examination can establish if an injury is UMN, LMN or mixed. Individuals with spinal cord injury, may have a diagnosis of cervical or thoracic injury which is typically indicative of a UMN injury, but not always. An injury to the brain or other neurological diseases may or may not have a UMN injury component. For example, an injury that affects motor function of the face can be a UMN injury. However, if the trauma is in the motor nerves of the brain stem or spinal cord area or to the peripheral nerves, the injury can be classified as a LMN to the face.

To determine if an injury is an UMN type with probable spasticity (tone), a medical evaluation needs to be conducted. This will include the following medical assessments:

Your medical history, including your family’s medical history to assess risk factors of UMN injury from disease or injury.

A physical examination.

A complete examination of the nervous system of the body. Aspects of the neurological examination include: mental status; sensory exam including the cranial nerves for sight, taste, hearing, smell as well as touch throughout the body, balance, and where the body is in space (proprioception); motor examination including strength, reflexes, and the ability of muscle groups to push and pull.

An EMG (electromyogram) examination which tests muscle function by application of a gentle electrical current to the muscle.

A NCS (nerve conduction study) is typically performed with an EMG. This test applies a gentle electrical current to a nerve to assess the nerve’s function. The electrical current may feel more powerful if there is damage to the nerve or to the coating of the nerve called myelin.

An MRI or CT scan is used to visually inspect the nerves within the body.

In spinal cord injury, a complete assessment of every nerve dermatome of the body is measured. This is part of the ASIA, or an updated name is the AIS, exam. The ASIA or AIS examination flow sheet can be seen here. If you have a spinal cord injury as a result of disease or injury, you will have periodic examinations using this assessment scale.

Assessment of Spasticity

Several measures are used to assess spasticity. The most common is the Modified Ashworth Scale for both adult and pediatrics. In the pediatric population, the Modified Tardieu Scale is sometimes used. These scales rely on a physical assessment by an educated professional. Mechanical devices are being developed to provide more control and less human error in the spasticity assessment process.

The Ashworth and Modified Ashworth Scales are the most commonly used measurements of spasticity (tone). The original Ashworth Scale was developed and is still in use today. The Modified Ashworth Scale refines one characteristic which provides more detail about spasticity. Notice, there are only whole number ratings. Occasionally, professionals will add + or – to each evaluation level however, these additional classifications are not defined in the scales. The assessment is performed by passive movement of an extremity to assess spasticity.

| SCORE | Ashworth Scale |

|---|---|

| 0 | No increase in tone |

| 1 | Slight increase in catch when limb is moved |

| 2 | Marked increase in tone, limb easily flexed |

| 3 | Passive movement difficult |

| 4 | Limb rigid |

| SCORE | MODIFIED ASHWORTH SCALE |

|---|---|

| 0 | No increase in muscle tone |

| 1 | Slight increase in muscle tone manifested by a catch and release or minimal resistance at the end of the range of motion when the affected part(s) are moved in flexion or extension |

| 2 | Slight increase in muscle tone, manifested by a catch, followed by minimal resistance throughout the remainder (less than half) of the ROM (range of movement) |

| 3 | More marked increase in muscle tone through most of the ROM, but affected part(s) are easily moved |

| 4 | Considerable increase in muscle tone, passive movement difficult |

| 5 | Affected part(s) rigid in flexion or extension |

The Tardieu Scale and Modified Tardieu Scale might be used in pediatric assessments of spasticity (tone). Assessment of spasticity is measured by muscle stretch at three different velocities: slow, with gravity and fast. The measurement notes the angle at the time of a ‘catch’ in movement. Assessment is performed at the same time of day and with the same positioning of the body. Joints assessed are the shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees and ankles. The quality of muscle reactions is measured as:

0 No resistance throughout passive movement

1 Slight resistance throughout

2 Clear catch at a precise angle

3 Fatigable clonus (<10secs)

4 Unfatigable clonus (>10secs)

5 Joint Immobile

Some newer kinematic (measurements of mass and force) devices have been developed to measure spasticity. These may consist of a variety of machines using limb placement and movement in a machine which controls consistency of timing and force of movement. Others may use electrodes for measurement of muscle function. These devices are starting to filter into general use, but most likely are found in research institutions or larger physical rehabilitation facilities.

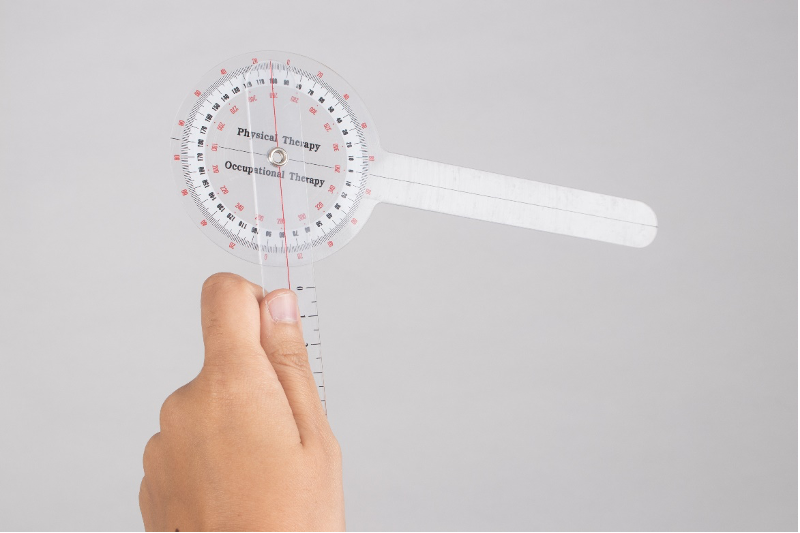

A goniometer is a plastic measuring device used to assess angle of joint movement. This device assesses the range of motion of a joint to identify a contracture. The device is placed against the skin along the area of a bone above and the bone below the joint. A protractor measurement indicates the angle of movement of the joint.

Treatment of Spasticity (Tone)

Treatment of spasticity (tone) varies depending on the severity and needs of the individual. Not everyone will want treatment. A mild case of tone can be used to benefit the individual. For example, some people use spasticity (tone) to assist with their transfers. Others use the spasticity movement to reduce the risk of development of pressure injuries or blood clots. Spasticity (tone) does not block these issues but the movement in the body assists individuals with a level of prevention. Pressure release movements and antiembolism preventions are still required.

When spasticity (tone) impedes activities of daily living, sleep or becomes annoying, painful, or prevents normal body functioning such as bladder, bowel, breathing or constricts body movement, treatment is sought. Physical therapies to treat spasticity (tone) are listed in the next section. Multiple alternatives are typically needed to effectively treat spasticity (tone).

Nonprescription treatments

Activity supplied to the body is an excellent treatment for spasticity (tone). This provides input to the muscle stretch reflex of each muscle. Exercise provides movement to the parts of the body affected by paralysis. The Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center provides information about how exercise should be added to your life.

Meditation, distraction and biofeedback are being used by individuals to help control their discomfort from spasticity. Self-calming measures are used to alter perceptions of discomfort.

Prescription treatments

Oral Medications

Medications taken by mouth are often prescribed to relax the muscles of the body. Common medications to treat spasticity (tone) include baclofen (Lioresal), clonazepam (Klonopin), dantrolene (Dantrium), diazepam (Valium), or tizanidine (Zanaflex). Finding the right medication and dose for you as an individual may require multiple changes and dosage adjustments.

Medications taken by mouth will affect every muscle in the body. Some individuals do not like this sensation. Others report ‘brain fog’ while on muscle relaxing medication. The body typically adjusts to these sensations over a short amount of time. Individuals begin with the lowest dose that controls their spasticity (tone). However, spasticity (tone) may increase over time requiring a person to periodically increase their oral medication. The body’s need to adjust to the medication will then be repeated.

Many individuals have had successful treatment using these medications and are content with them. However, due to new addiction guidelines, some individuals are being required to alter their treatment plan to other alternatives. This can be disruptive when you have a treatment that works well. Do not suddenly stop taking oral medication for spasticity (tone). A tapering program is needed to avoid withdrawal symptoms. Also, stopping suddenly will increase your spasms as well as making them more difficult to treat in the future. Finding an alternative can take some time. Occasionally, individuals find that when they taper off their medication, spasticity (tone) has resolved and no further treatment is needed.

Injectable Medications

Due to the side effects of oral medications, many individuals have opted for injectable treatments. The common medications used currently are onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) and abobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport). These medications slightly weaken the muscle reducing its ability to spasm. The muscle does recover which leads to the need to have these injections periodically repeated about every six months. For some cases, the injection cycle can be as often as every three months.

Injectable treatments stay in the area where the injection is delivered. There are very rare occasions where the injected medication has traveled to other parts of the body. Because the medication stays in the treated spasming muscle, the side effects of oral medication are removed. Injectables for spasticity (tone) treatment have been used in the arms, legs, bladder, abdomen as well as other areas of the body.

Nerve blocks are injected medication to the area where a single nerve is the source of your spasticity. This can temporarily slow the function of the nerve so spasticity cannot occur. These injections need to be repeated to maintain spasticity (tone) reduction,

Nerve blocks with phenol destroy the nerve at the muscle which stops the spasticity. This is not often performed today as it has been in the past due to destruction of the nerve. This type of injection is not repeated as the nerve is destroyed.

Electrical Stimulation

Surface stimulation of nerves can be obtained by using a nerve stimulator which transmits impulses through an electrode(s) on the surface of the skin. This portable device is used to relax the muscle and interrupt the spasticity activity of the nerve. A transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit is used. Various TENS units and settings will need to be tried to see if a product will reduce your spasticity (tone).

Surgical Treatments

Implantable Devices

Occasionally, spasticity (tone) becomes so strong that oral or injectable medications are not able to control the spasming muscles. A pump surgically implanted into the abdomen is a higher-level alternative. This pump has a tube that is placed in the body from the pump to the spinal canal. The pump slowly delivers spasm reducing medication, typically baclofen, into the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) that bathes the spinal cord. The medication is heavier than CSF, so it stays in the lower spinal cord avoiding respiratory complications. An external magnet is placed over the skin to adjust the pump’s dosing amounts or even vary the doses throughout the day based on your activity schedule.

The pump medication is delivered in higher amounts than could be taken orally. Most often this treatment is used for spasticity in the lower body. There are a few neurosurgeons who can place the pump higher to assist with arm spasticity as well. A pretest is performed to establish if the pump is the right treatment for you.

The pump needs to be refilled at intervals. If neuropathic pain is also an issue, a combination of medications can be used to control both spasticity (tone) and neuropathic pain.

Spinal electrical stimulation implants are currently being used in research settings. The goal is to improve functional outcomes, but the results have indicated they also decrease spasticity. This might be due to increased use of muscles or stimulation of the nerves in the spinal cord. This form of treatment will be available to everyone soon.

Surgery

If spasticity (tone) begins to affect the ability to stretch a muscle, tendon releases or tendon lengthening can be performed in a surgical procedure. This includes a feathering of the tendon to relax the pull on the muscle. After the surgery, casting, splints or braces are used to hold the tendon in place until it is healed.

One type of surgery that is used to control spasticity in children with cerebral palsy is selective dorsal rhizotomy. Using general anesthesia, each peripheral nerve of the cauda equina is evaluated to establish which are the source of spasticity. Once identified, individual nerve fibers (not the entire nerve) are disconnected leaving functional nerve transmission intact. A specialized neurosurgeon performs this operation.

Because spasticity (tone) treatments are so successful, rarely is surgery used to sever a nerve that leads to an individual’s spasticity. However, in some difficult to treat cases this type of surgery is still an option. Currently, it is only seen in people who were treated in the past. The result is a flaccid muscle.

Therapy for Spasticity (Tone)

Physical therapy techniques are used as a part of the total treatment plan for spasticity (tone). These techniques can be used in the home setting.

Gentle stretching of the area affected by spasticity can fatigue the muscle which relaxes the spasticity (tone). Sharp, jerky motions increase spasticity (tone). Gentle movement, when performing range of motion exercises stretches the muscle to keep it from contracting or shortening.

Casting, splints and braces are used to keep muscles stretched which avoids contractures or shortening of the muscle.

Strengthening muscles helps to restore the balance between pushing and pulling muscles. Strong muscles are less susceptible to spasticity.

Standing engages the muscles by putting body weight through them. This helps stretch the muscles making them less susceptible to spasm. A standing frame is used to support the body in an upright position.

Whole body vibration is a therapeutic treatment that gently mechanically oscillates the body through a device. The vibration is thought to decrease the excitation of the spastic muscle.

Electrical stimulation can be used to interrupt spasticity patterns or to fatigue a muscle.

Cold/Heat therapies should be used under the guidance of a therapist. Cold may temporarily reduce the spasm of the muscles whereas heat may temporarily relax the muscle. This treatment can lead to complications if you have reduced sensation that does not inform you that the treatment is causing damage to your body.

Acupuncture and meditation have been used effectively to reduce spasticity (tone) by some individuals.

Rehabilitation Professionals Involved in the Treatment of Spasticity (tone)

Those involved in your rehabilitation for spasticity include:

The Physiatrist (a physician who specializes in physical rehabilitation) or primary care healthcare provider. This individual will diagnose and follow your progress in treatment of spasticity. They will order therapies, medications and other treatments as needed for your individual condition.

The Physical Therapist will provide treatments for spasticity including strengthening and major body therapies.

The Occupational Therapist will provide treatments for spasticity including treatments to local areas of concern.

The Rehabilitation Nurse will assist you in understanding your treatment options and monitor your progress.

Research

Issues of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) after spinal cord injury include spasticity (tone), neuropathic pain and autonomic dysreflexia among others. These three issues are being studied in conjunction in an attempt to find one treatment that positively affects them all. Current studies in rats indicate that gabapentin, a treatment for neuropathic pain, may also treat and reduce spasticity (Rabchevsky, et al. 2010, 2011). A one-treatment approach to control various ANS issues would reduce the numbers of medications required, decrease drug interactions, as well as enhance control of these issues.

Spinal electrical implants are under study in people with spinal cord injury. One of the results of these clinical trials is reduced spasticity (tone). How this works is not clearly understood however, use of the nerves and muscles as produced by the electrical implant affects the overall function of the body (Elbasiouny, 2010).

Research is being conducted to aid in the understanding of spasticity and to understand existing and new treatments and diagnoses. What is discovered in one area of neurology is then translated into improvements for individuals with spasticity from other types of neurological diagnoses. You can find more information about clinical trials about spasticity at the following site from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. If you are looking for information about spasticity research, would like to volunteer or just want to know what is being studied, this site is loaded with specific information.

Facts and Figures

Estimates of the number of individuals with spasticity (tone) are 500,000 in the US and over 12 million worldwide. As there is no central reporting system for spasticity, numbers are unclear. These estimates are significantly lower than actual numbers.

Figures for spasticity after stroke are elusive due to the numbers of individuals affected and due to incomplete reporting. For individuals with stroke (Cerebral Vascular Accident) spasticity is reported in 30% to 80% of individuals. From the time of stroke onset, at one month the rate of spasticity is 27%, at three months 28%, at six months 23%-43%, and at 18 months 34%. Spasticity (tone) can be in any muscle after stroke. It is more often in the flexing muscles of the fingers, wrist (66%), elbow (79%), and shoulder (58%). Spasticity (tone) is usually in the extending muscles of the leg. In the ankle, it is present in 66% of individuals (Kuo, 2018).

Cerebral Palsy occurs in 1-4 per 1,000 live births. About 70-76% have the spastic type of cerebral palsy (CDC, retrieved 2021).

Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis have a rate of spasticity at 60%-80%. (https://www.nationalmssociety.org/ retrieved 2021)

Individuals with Brain Injury have a rate of spasticity at 50%. (https://msktc.org/tbi/factsheets/spasticity retrieved 2021)

Individuals with spinal cord injury are noted to have spasticity (tone) at a rate of 65-75%. Individuals with cervical and thoracic spinal cord injury have greater incidences of spasticity (MSKTC, retrieved 2021)

Consumer Resources

If you are looking for more information about spasticity or have a specific question, our Information Specialists are available business weekdays, Monday through Friday, toll-free at 800-539-7309 from 9:00 am to 8:00 pm ET.

Additionally, the Reeve Foundation maintains a spasticity booklet and fact sheet with additional resources from trusted Reeve Foundation sources. Check out our repository of fact sheets on hundreds of topics ranging from state resources to secondary complications of paralysis.

We encourage you to reach out to paralysis-related support groups and organizations, including:

Associations which feature news, research support, and resources, national network of support groups, clinics, and specialty hospitals.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

US National Library of Medicine: Clinical Trials.gov

National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health: PubMed

Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center https://msktc.org/sci/factsheets/Spasticity and https://msktc.org/sci/factsheets/exercise

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Further Reading

Adams M, Hicks A. Spasticity after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 43, 577–586 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101757

Banky M, Williams G. Tardieu Scale. J Physiother. 2017 Apr;63(2):126. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2017.01.002. Epub 2017 Feb 16. PMID: 28325481.

Chou R, Peterson K, Helfand M. Comparative efficacy and safety of skeletal muscle relaxants for spasticity and musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004 Aug;28(2):140-75. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.05.002. PMID: 15276195.

Elbasiouny S M, Moroz D, Bakr M M, Mushahwar V K. (2010). Management of spasticity after spinal cord injury: current techniques and future directions. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 24(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968309343213

Enslin JMN, Langerak NG, Fieggen AG. The evolution of selective dorsal rhizotomy for the management of spasticity. Neurotherapeutics. 2019 Jan;16(1):3-8. doi: 10.1007/s13311-018-00690-4. PMID: 30460456; PMCID: PMC6361072.

Fernández-Tenorio E, Serrano-Muñoz D, Avendaño-Coy J, Gómez-Soriano J. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for spasticity: A systematic review. Neurologia. 2019 Sep;34(7):451-460. English, Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2016.06.009. Epub 2016 Jul 26. PMID: 27474366.

Khan F, Amatya B, Bensmail D, Yelnik A. Non-pharmacological interventions for spasticity in adults: An overview of systematic reviews. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2019 Jul;62(4):265-273. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2017.10.001. Epub 2017 Oct 16. PMID: 29042299.

Kuo, C-L, Hu, GC. Post-stroke spasticity: A review of epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatments. International Journal of Gerontology, Volume 12, Issue 4, 2018, Pages 280-284, ISSN 1873-9598, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijge.2018.05.005.

Lee KC, Carson L, Kinnin E, Patterson V. The Ashworth Scale: A reliable and reproducible method of measuring spasticity. J Neuro Rehab 1989; 3:205–209.

Meseguer-Henarejos AB, Sánchez-Meca J, López-Pina JA, Carles-Hernández R. Inter- and intra-rater reliability of the Modified Ashworth Scale: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2018 Aug;54(4):576-590. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.17.04796-7. Epub 2017 Sep 13. PMID: 28901119.

Mukherjee A, Chakravarty A. Spasticity mechanisms – for the clinician. Front Neurol. 2010;1:149. Published 2010 Dec 17. doi:10.3389/fneur.2010.00149

Picelli A, Santamato A, Chemello E, Cinone N, Cisari C, Gandolfi M, Ranieri M, Smania N, Baricich A. Adjuvant treatments associated with botulinum toxin injection for managing spasticity: An overview of the literature. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2019 Jul;62(4):291-296. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2018.08.004. Epub 2018 Sep 13. PMID: 30219307.

Sivaramakrishnan A, Solomon JM, Manikandan N. Comparison of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and functional electrical stimulation (FES) for spasticity in spinal cord injury – A pilot randomized cross-over trial. J Spinal Cord Med. 2018 Jul;41(4):397-406. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2017.1390930. Epub 2017 Oct 25. PMID: 29067867; PMCID: PMC6055976.

Synnot A, Chau M, Pitt V, O’Connor D, Gruen RL, Wasiak J, Clavisi O, Pattuwage L, Phillips K. Interventions for managing skeletal muscle spasticity following traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 22;11(11):CD008929. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008929.pub2. PMID: 29165784; PMCID: PMC6486165.

Thibaut A, Chatelle C, Ziegler E, Bruno MA, Laureys S, Gosseries O. Spasticity after stroke: physiology, assessment and treatment. Brain Inj. 2013;27(10):1093-105. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.804202. Epub 2013 Jul 25. PMID: 23885710.

Trompetto C, Marinelli L, Mori L, Pelosin E, Currà A, Molfetta L, Abbruzzese G. Pathophysiology of spasticity: implications for neurorehabilitation. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354906. doi: 10.1155/2014/354906. Epub 2014 Oct 30. PMID: 25530960; PMCID: PMC4229996.

Rabchevsky AG, Patel SP, Duale H, Lyttle TS, O’Dell CR, Kitzman PH. Gabapentin for spasticity and autonomic dysreflexia after severe spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011 Jan;49(1):99-105. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.67. Epub 2010 Jun 1. PMID: 20514053; PMCID: PMC2953609.

Rabchevsky AG, Kitzman PH. Latest approaches for the treatment of spasticity and autonomic dysreflexia in chronic spinal cord injury. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8(2):274-282. doi:10.1007/s13311-011-0025-5