Post-Polio Syndrome

Polio was an epidemic in the United States in the 1940s and 1950s. People in the United States do not often contract polio because of the development of a polio vaccine which was developed in 1955 by Jonas Salk and an oral vaccine in 1962 by Albert Sabin. Vaccinated individuals cannot host a virus which makes it unable to replicate and spread. The polio virus is still active in some areas of the world. Improved sanitation measures have also helped to control it.

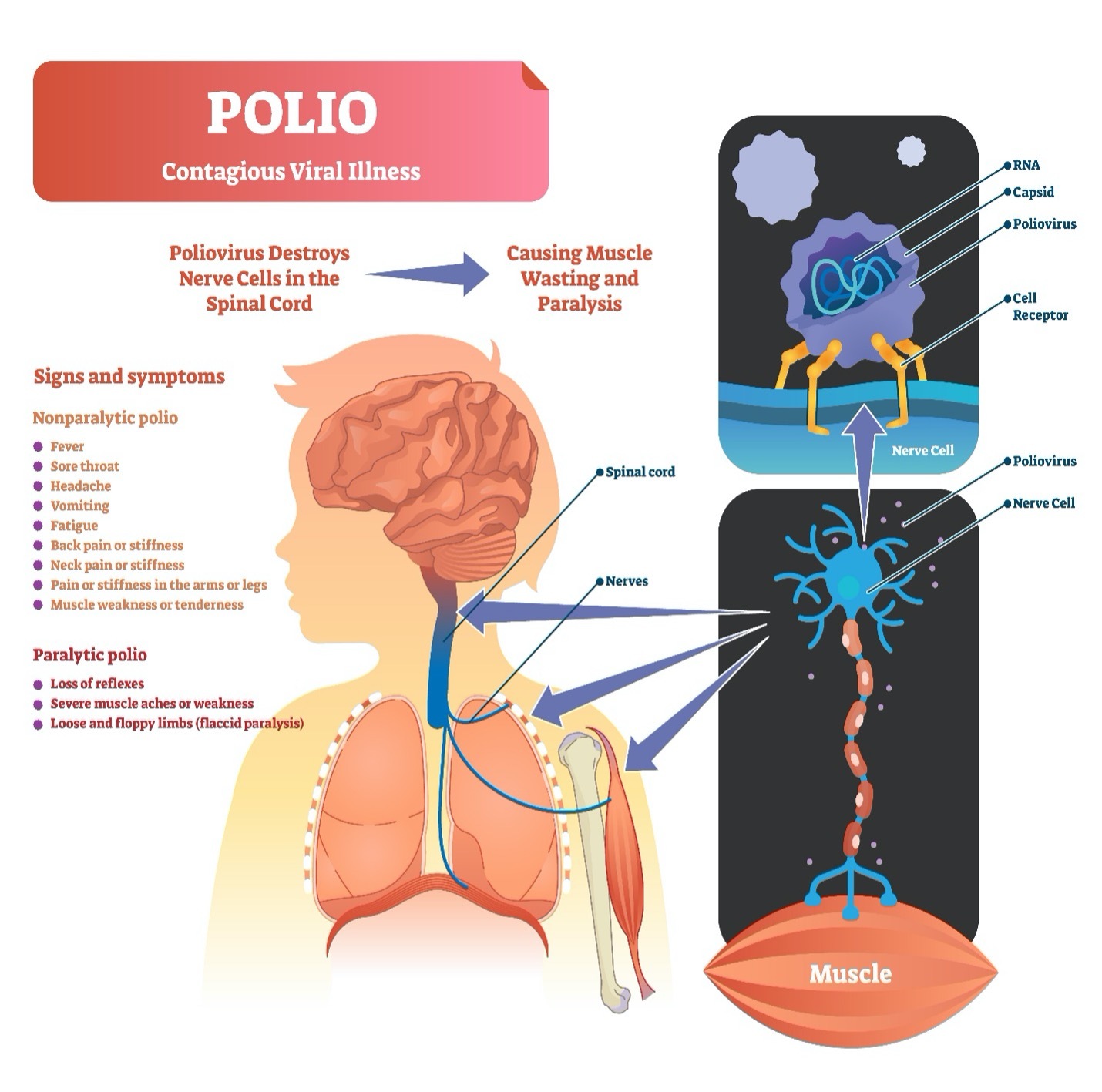

Poliomyelitis or polio is a contagious virus that enters the body. It is spread in respiratory droplets and through solid body waste. Most individuals who have polio will have flu-like symptoms. Rarely, polio affects the motor nerves (nerves that control movement) of the body especially in the spinal cord. This can be a sensation of tingling (paresthesia), an infection in the covering of brain and spinal cord (meningitis), or weakness in the muscles of the body (paralysis). Motor nerves are affected by polio which can lead to paralysis anywhere in the body with decreased movement seen in the arms and legs and most notably in the muscles that control breathing.

Some individuals survived the polio epidemic. Those with motor nerve damage may have some residual movement deficits. To accommodate the loss of movement, affected nerve fibers develop new nerve-end terminals (dendrites) that will connect with other nearby muscle fibers. The result is functional movement recovery. This process is a representation of neuroplasticity or the ability of the nervous system to recover by developing nerve buds to improve the strength of the polio affected nerve fibers and muscles. After the initial polio episode, the individual can have partial to what appears to be a full recovery.

Over time, some individuals with a history of polio which affected the motor nerves may develop new muscle pain, weakness, or paralysis 10 to 40 years after the original polio episode. This is post-polio syndrome (PPS). Years later, the overused motor nerves become unable to keep up with movement demands which results in their slow deterioration. There may be some improvement a second time, but eventually, the nerve terminals slowly malfunction without further recovery. Progressive weakness and paralysis can occur.

It is important to note that only a small number of individuals develop post-polio syndrome. Those that survived polio without motor nerve involvement do not develop PPS. Post-polio syndrome is not contagious. It is not a re-activation of the virus but rather an effect of deterioration of the replacement or supplemental nerves.

Symptoms and Risk Factors of Post-Polio Syndrome

Post-polio syndrome tends to develop slowly with alternating periods of stability followed by increasing symptoms. The development of PPS occurs over time.

PPS occurs in individuals with a history of polio that included motor nerve involvement. It is typically not life-threatening unless breathing is affected and untreated. Individuals differ in amount of affected function. Some will have mild cases of PPS with minor adaptions while others will have more significant issues requiring changes in lifestyle.

Symptoms include some or all of these factors:

- progressive weakness in muscles and joints

- pain in muscles and joints

- body/mind fatigue and exhaustion with minimal activity

- loss of appetite

- fever

- muscle atrophy (wasting)

- bone distortions such as scoliosis (curving of the spine)

- breathing issues

- sleep disorders, insomnia, sleep apnea

- swallowing issues

- cold temperature intolerance, occasionally intolerance to heat

Risk Factors for Post-Polio Syndrome

Risk factors for PPS include a higher incidence in those individuals who had a severe initial course of polio with motor nerve involvement. If recovery of function was good or excellent from the initial polio event, more stress is placed on the supplementing nerves which can lead to post-polio syndrome motor nerve failure. Development of polio later in life as a teen or adult can relate to a higher risk of PPS because the sprouting nerve terminals are slower to develop as individuals age. Overexercising to the point of muscle fatigue can be a trigger for PPS if you have a history of polio with motor nerve involvement.

Complications of Post-Polio Syndrome

Issues that result from PPS depend on location of injury to the nerve such as in the spinal cord, in the body or both. Complications arise as weakness progresses. These are some of the key issues.

- Falls: muscle weakness can lead to balance problems, slipping or getting your toe caught under a rug or stair step. Falls can have profound consequences such as pulled muscles, bruising, and broken bones.

- Difficulty swallowing: individuals with PPS that affects oral motor activity such as chewing and swallowing can lead to nutritional issues and dehydration. Poor oral motor control can lead to pneumonia if food is misdirected into the lungs.

- Breathing: issues arise due to weak chest and abdominal muscles. This can reduce the ability to produce a strong cough to clear airway passages which can lead to pneumonia. Muscular changes can lead to breathing issues such as sleep apnea or chronic respiratory failure.

- Muscle and skeletal structure: changes from strong muscles pulling the body against weaker muscles can result in structural bone changes leading difficulty in body positioning, discomfort, pain, contractures, difficulty in hygiene. Muscular changes can lead to breathing issues such as sleep apnea or chronic respiratory failure as well as pressure injury. Scoliosis, a change in the structural positioning of the spine affects the body’s ability to inhale deeply and effectively.

- Neurogenic bowel and bladder: nerve miscommunications change your ability to toilet. Bowel and bladder programs can be established to keep your body healthy. These programs reduce complications and maintain continence if elimination is challenged.

- Bone mineral density: reductions from skeletal changes or inactivity can create osteopenia (low bone mass) or osteoporosis (extremely low bone mass).

- Assistive device: issues such as braces and splints rubbing on the skin or use of crutches can lead to pressure injury and joint pain.

Diagnosing Post-Polio Syndrome

Your healthcare provider will perform a complete physical examination and health history. They will be differentiating your symptoms from other neurological issues. Clues to PPS include a history of polio specifically affecting the motor nerves followed by partial or complete recovery for a period of 10 years or more.

The history of PPS includes a new onset of slowly progressive muscle weakness, decreased endurance, muscle atrophy, muscle and/or joint pain and fatigue. Typically, later developing symptoms include breathing or swallowing issues. Onset of PPS is gradual but inactivity from trauma or surgery can make the symptoms appear suddenly. Even though you see your healthcare provider early, a diagnosis of PPS is typically not made until symptoms have been in process for a minimum of a year.

Questions about other health concerns that could be similar to PPS symptoms will be asked. These include issues with depression which affect activity levels or functional issues such as joint pain from use of braces or crutches. Some of the symptoms of PPS are stand-alone medical conditions, such as breathing dysfunction or scoliosis, and are therefore not conclusive symptoms for PPS.

Included in your healthcare professional’s physical examination is manual muscle testing (MMT) where the strength of each of your major muscle groups is assessed and rated. This is done by the provider in their office at a usual visit. You are asked to push or pull muscle groups against the resistance of the examiner. Some instruments may be used for more precise measurements.

An electromyography (EMG) test is done to establish motor neuron loss. This is performed on any muscle of the body by using a sensor or needle to assess electrical conduction to the muscle by the nerve. Nerve conduction studies (NCS) may or may not be done depending on individual circumstances.

Imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) of the spine can follow progression of PPS.

A muscle biopsy might be done to exclude other diagnoses.

There are no laboratory blood tests used to diagnose PPS.

There is no test that predicts which survivor of polio with affected motor nerves is at risk for PPS.

Rehabilitation for Post-Polio Syndrome

Treatment for PPS depends on individual issues. Rehabilitation programs are developed for the unique needs of the individual depending on issues that develop and prevention strategies.

Energy conservation is the focus of rehabilitation strategies for individuals with post-polio syndrome. This may involve some changes in lifestyle. You may need to add rest periods into your day to ensure you are not overexerting your muscles. It may be necessary to use adaptive equipment for mobility. Perhaps you can walk some distance but become fatigued when doing so. Using adaptive equipment such as a wheelchair for distance use might make your day more functional when you are not fatigued from walking. The goal is to not fatigue your muscles to the point of creating more nerve damage. Maintain a healthy weight to reduce your workload.

Avoid falls by wearing properly fitted shoes, pick up clutter especially on the floor, use handrails when going up or down stairs, remove throw rugs, avoid slippery or icy walkways, use mobility aids as necessary for safety.

Exercise is critical to health, but over-exerting muscles leads to increased muscle fatigue. Less strenuous exercises can be provided to keep your muscles functional without overexertion. Light swimming is a good total body exercise. Cardiopulmonary exercise is preferred to fatiguing strengthening exercise. An exercise plan should be developed that will avoid ache, fatigue, and weakness. The exercise program should be tailored to your needs to include muscles to be strengthened, muscles to avoid exertion and frequency of the program.

Strengthening oral motor skills is helpful. Tucking your chin when swallowing can be useful to avoid choking. Exercises can be performed to help increase your oral muscles for speaking, eating, and swallowing. These can increase your communication ability as well as to protect your airway when eating.

Breathing is a critical activity. Decreased ventilation affects your body through fatigue and mental acuity. Use of sleep apnea devices should be initiated if that is an issue. This is helpful to avoid cardiac complications. Mechanical ventilation that is used continuously or for rest periods can be provided. There are a variety of mechanical ventilation devices that can be used. Some require intubation but many others do not. Your healthcare team can find the type of device that is right for your needs. Stop smoking to keep your lungs healthy. Report respiratory infections promptly for quick treatment. Keep up to date with flu and pneumonia vaccines.

Pain control using analgesics or nerve pain medication may be helpful. For some, anti-inflammatory medications have been helpful. If nerve pain is an issue, gabapentin (Neurontin) and pregabalin (Lyrica) as well as low dose anti-seizure medication and low dose anti-depressants are useful.

Body temperature is affected by PPS. Stay warm by keeping your environment at a comfortable temperature, dress in layers; if doing aquatic therapy, use a heated pool. Keep a comfortable temperature in the summer months but avoid overdoing air conditioning to avoid cold intolerance.

Those who will be involved with your care are:

Your Primary Healthcare Provider will take care of your daily needs. They will guide you in the care of general healthcare issues.

A Neuromuscular Physician Specialist is a specially educated neurological physician who will take the lead about issues of PPS. This person will follow your progress to provide the best treatments for PPS.

A Pulmonary Medical Specialist can assist with assessing breathing ability and equipment that may be required, if any.

Physical Therapists will provide therapy to gently increase your strength and balance. They can assist with energy conservation principles. The physical therapist can help you select mobility aids, if needed.

Occupational Therapists will assist with adaptations to increase your function in daily living both through gentle strengthening and adaptive equipment. They can assist with energy conservation techniques.

Speech Therapists can assist with improving oral motor function and speech clarity if these are issues. This individual will help you learn how to keep your airway clear.

Respiratory Therapists will assist with strengthening your breathing ability as well as help you learn to use the correct equipment if breathing is an issue.

A Psychologist, Counselor or Social Worker can assist with adaption to chronic illness. They can help provide skills to deal with issues as they arise and provide strategies to deal with challenges prior to occurring.

Rehabilitation Specialty Registered Nurses can assist with understanding your symptoms, treatments, medication, and management of personal care such as bowel and bladder programs, if needed. They will assist you with translating information from other specialists into your life.

Insurance Case Managers are professionals who will assist with translation of what your payor/health insurer will assist with during your rehabilitation.

Preventing Post-Polio Syndrome

Post-polio syndrome develops in individuals who have survived polio that impacted motor nerves. There is no vaccine or other medication that can prevent post-polio syndrome nor is there a way to predict who will develop it. Risk factors are indicators of possibility, not direct indicators of development of the syndrome.

If you survived polio that affected your motor nerves (those for movement and breathing), you can implement energy conservation techniques and conservative exercise perhaps to slow the onset of PPS. This is not a proven prevention because no one knows who will develop PPS and who will not.

The best prevention of PPS is to avoid getting polio. This can be done by getting the polio vaccine. There are two types of vaccine that are given to children. One is the oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) that is given around the world. In the United States, only the inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPC) series has been given since the year 2000. The polio vaccines prepare the body to fight poliovirus should exposure occur. It provides protection of 99% if the entire series of vaccinations are completed.

Research of Post-Polio Syndrome

The number of studies of post-polio syndrome are vast. Initially, scientists began looking at the source and causes of PPS particularly of the motor neurons without and after polio including the neuron junction to the muscles. They continue to pursue and understanding of the source of PPS. Immunological studies of polio resulting due to inflammation as an immune response is also under review.

The consequences of PPS such as fatigue are being researched to understand the causes and to develop treatments that will assist in improvements of quality of life and function.

Preliminary studies have been performed with various treatments at the National Institutes of Health Preliminary studies means there were small numbers of participants with these beginning studies. The outcomes are not yet demonstrated for general use. The preliminary studies are listed below with outcomes. More research will be conducted.

| Drug | Outcome |

| Prednisone | Some individuals noted improvement, but these results were not significant (no more than chance) |

| Intravenous Immunoglobulin | May reduce pain and increase quality of life |

| Lamotrigine (an anticonvulsant drug) | Possibly effective in treating fatigue, but a larger study needs to be conducted, evidence not conclusive. |

Facts about Post-Polio Syndrome

Post-polio syndrome is not contagious. It is not caused by a virus. It is the result of previously damaged nerves from the initial polio event.

Over 12 million people, worldwide have been affected by polio as indicated by the CDC.

There is no central system for reporting post-polio syndrome, but it is estimated that 300,000 individuals are survivors of polio in the United States and have mild to severe symptoms.

Of the 300,000 survivors of polio, it is estimated that of one fourth to one half may develop some form of post-polio symptoms.

It appears that individuals who had severe cases of motor nerves affected by polio may be more likely to develop post-polio syndrome.

Resources

If you are looking for more information about post-polio syndrome or have a specific question, our Information Specialists are available business weekdays, Monday through Friday, toll-free at 800-539-7309 from 9:00 am to 8:00 pm ET.

Additionally, the Reeve Foundation maintains a post-polio fact sheet with additional resources from trusted Reeve Foundation sources. Check out our repository of fact sheets on hundreds of topics ranging from state resources to secondary complications of paralysis.

We encourage you to reach out to post-polio support groups and organizations, including associations which features news, research support, and resources, national network of support groups, clinics, and specialty hospitals.

Post-Polio Health International

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)

https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Post-Polio-Syndrome-Information-Page

National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD)

Further Reading

Bromberg MB, Waring WP. Neurologically normal patients with suspected postpoliomyelitis syndrome: electromyographic assessment of past denervation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991 Jun;72(7):493-7. PMID: 2059122.

Curtis A, Lee JS, Kaltsakas G, Auyeung V, Shaw S, Hart N, Steier J. The value of a post-polio syndrome self-management programme. J Thorac Dis. 2020 Oct;12(Suppl 2):S153-S162. doi: 10.21037/jtd-cus-2020-009. PMID: 33214920; PMCID: PMC7642628.

Ghavanini MR, Ghavanini AA. Fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves in patients with antecedent paralytic poliomyelitis. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998 Dec;38(8):455-8. PMID: 9842478.

Grimby G, Li J, Vandenakker C, Sandel ME. Post-polio syndrome: a perspective from three countries. PM R. 2009 Nov;1(11):1035-40. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.09.005. PMID: 19942191.

Halstead LS. Assessment and differential diagnosis for post-polio syndrome. Orthopedics. 1991 Nov;14(11):1209-17. PMID: 1758788.

Lo JK, Robinson LR. Postpolio syndrome and the late effects of poliomyelitis. Part 1. pathogenesis, biomechanical considerations, diagnosis, and investigations. Muscle Nerve. 2018 Dec;58(6):751-759. doi: 10.1002/mus.26168. Epub 2018 Aug 22. PMID: 29752819.

Lo JK, Robinson LR. Post-polio syndrome and the late effects of poliomyelitis: Part 2. treatment, management, and prognosis. Muscle Nerve. 2018 Dec;58(6):760-769. doi: 10.1002/mus.26167. Epub 2018 Aug 23. PMID: 29752826.

Jonathan Ramlow, Michael Alexander, Ronald LaPorte, Caroline Kaufmann, Lewis Kuller, Epidemiology of the post-polio syndrome. American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 136, Issue 7, 1 October 1992, Pages 769–786, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/136.7.769

Sheth NP, Keenan MA. Orthopedic surgery considerations in post-polio syndrome. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2007 Jul;36(7):348-53. PMID: 17694181.

Tiffreau V, Rapin A, Serafi R, Percebois-Macadré L, Supper C, Jolly D, Boyer FC. Post-polio syndrome and rehabilitation. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010 Feb;53(1):42-50. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2009.11.007. Epub 2009 Dec 30. PMID: 20044320.

Trojan DA, Gendron D, Cashman NR. Electrophysiology and electrodiagnosis of the post-polio motor unit. Orthopedics. 1991 Dec;14(12):1353-61. PMID: 1784551.

Voorn EL, Koopman FS, Brehm MA, Beelen A, de Haan A, Gerrits KH, Nollet F. Aerobic exercise training in post-polio syndrome: Process evaluation of a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2016 Jul 15;11(7):e0159280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159280. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2018 Jan 30;13(1):e0192338. PMID: 27419388; PMCID: PMC4946776.