Friedreich Ataxia

Friedrich Ataxia is an encompassing term for medical conditions that affect the coordination of the body. Friedreich ataxia is a particular type of coordination issue that is caused by an extremely rare degenerative disease that is inherited. In Friedreich ataxia, nerves are affected in the central nervous system, particularly in the cerebellum of the brain which controls coordination, and in the spinal cord in efficient sending of messages to and from the brain and body. Also affected are the peripheral nerves (nerves in the body outside of the brain and spinal cord). These changes in nerve function cause unsteady and jerky body movements as well as loss of sensation.

Associated medical issues of Friedreich ataxia include cardiac problems, pancreatic function leading to diabetes, and muscle imbalance causing scoliosis among other issues. These conditions should be monitored and controlled to delay onset. Issues with oral motor functions such as slurred speech, hearing loss, and vision problems may occur if those nerves are affected.

Not affected by Friedreich ataxia are thinking, reasoning, and learning abilities. Individuals with Friedrich Ataxia have no more effects on learning than any other person.

Friedreich ataxia typically is most often first noted between the ages of five and 15, however, in some instances, development of the condition is not noted until later in life. Late-onset Friedreich ataxia (LOFA) is diagnosed by age 25 but a small number of individuals do not have symptoms until age 40 which is very late onset Friedreich ataxia (VLOFA). Individuals with a later onset of symptoms generally have a slower progression of the disease.

Life expectancy varies by time of onset, the ability to ambulate, and control of subsequent medical conditions. Those with later onset and those with ambulatory ability have longer lifespans. The lifespan range for individuals who have Friedreich ataxia can significantly vary between the 30-year decade through the 70-year decade and beyond.

Genetics

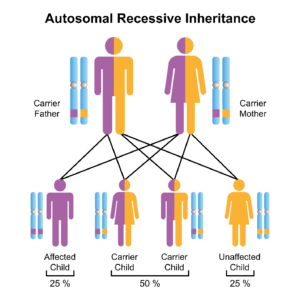

Friedreich ataxia is a recessive genetic disease. This means both parents must be carriers of the recessive gene for the disease to be present in the child. Having just one parent with the recessive disease will not produce it in the child. Assessment of both the male and female genetic background is needed if there is a suspicion of genetic diseases such as Friedreich ataxia.

The following graphic represents the transmission possibilities of Friedreich ataxia:

Symptoms/Diagnosis

There are some common characteristics of Friedreich ataxia. The symptoms and severity of the disease vary by individual with the effects of the FXN genes. Commonalities are present but individuals will have some differences. Some will have all symptoms while others may have only a few.

Symptoms of Friedreich ataxia most commonly include the following:

-

- Impaired balance or coordination (jerking) of body movements especially in the trunk and limbs

-

- Progressively staggering gait or decreased ability to walk

-

- Diminishing or loss of deep tendon reflexes

-

- Falling

-

- Dysarthria (difficulty speaking and controlling oral motor function)

-

- Loss of proprioception (awareness of the body in space)

-

- Loss of sensation, usually beginning in the feet and evolving up the body

-

- Fatigue

-

- Tone/spasticity

-

- Speech (slow or uncoordinated)

-

- Swallowing difficulty

-

- Hearing loss

-

- Vision issues

-

- Cardiac issues most often include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (thickened heart muscle) but may also include myocarditis (inflammation), heart muscle scarring, enlarged heart, congestive heart failure, fast heart rate, irregular heart beating, and heart block

-

- Diabetes mellitus with insulin resistance and pancreatic ß-cell dysfunction

-

- Musculoskeletal issues such as scoliosis, high arch in the foot, clubfoot

Diagnosing Friedreich ataxia begins with genetic testing of the parents before conception. This will inform the parents of the odds of the disease being present in the child. The parents will be able to make decisions about conception and alternatives.

If there was no known suspicion of risk or family history of Friedreich ataxia, genetic testing most likely would not have been completed. A healthcare professional may utilize genetic testing of the individual to confirm a diagnosis. The same may be performed later in life as late-onset symptoms appear.

A complete physical and neurological examination provides information about the body systems that are affected.

Once the diagnosis of Friedreich ataxia is determined, by genetic testing or clinical diagnosis, monitoring is conducted to determine the presence and control of the effects in different body systems. Common testing includes:

Nervous System

-

- Annual neurological examination

-

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans for cerebellar and spinal cord atrophy

-

- Electromyogram (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (NCS) to assess nerve and muscle function in the body

Cardiac System

-

- Annual cardiac examination

-

- Electrocardiogram (EKG) to assess heart function

-

- Echocardiogram to assess heart contractions

-

- Holter monitor testing for heart dysfunction

Orthopedic System

-

- Annual X-ray of the spine for scoliosis

Ophthalmology

-

- Annual eye exam

Audiology

-

- Annual hearing exam

Immunological System

-

- Inoculations for flu, RSV, COVID, and pneumonia as needed

Blood Tests

-

- Blood sugar, fasting blood sugar, A1C to assess for diabetes and vitamin E levels.

-

- Hemoglobin to assess blood oxygenation

Therapy

-

- Physical, Occupational, Speech and Language therapy for improvement in neurological, orthopedic, and oral motor concerns

-

- Mental health assessment and treatment as needed

Assessment scales are used to assess the effects of disease in people as well as to track the progression, stability, or improvement of diseases. The most commonly used assessment scales to follow the progress of individuals with Friedreich ataxia are the Friedreich’s Ataxia Rating Scale (FARS) and the Modified Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale (mFARS). These scales are administered by educated professionals, not for home use. If you would like to review the scales, the mFARS guidelines can be downloaded as a PDF here.

Treatments

A recently approved drug omaveloxolone (SkyclarysTM) was approved for use in individuals who are age 16 years and older with Friedreich ataxia. It is used to treat disease progression, with slowing of the disease estimated by more than two years. Special requests for use in children have been obtained. Data are being collected to include children in the use of the drug. Information about this product can be found on the production company website: https://hcp.skyclarys.com/?utm_source=aw_sbr_paidsearch&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=rteskyc_hcp_sem_crs_aw_sbr_nat_awa_ext&utm_keyword=skyclarys-prescribing-information&utm_id=rteskyc13770&gclid=Cj0KCQiA1rSsBhDHARIsANB4EJYuTM7hudeMv7il95qnGUWp2fQzJw9IJWulAhokfwKMkUHGFPJhuXwaAqgtEALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds

The Friedreich Ataxia Research Alliance provides a better understanding of rare disease medications in general. It can be found here: https://www.christopherreeve.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/RareDiseaseMedicationFAQs.pdf

Supplements such as antioxidants, vitamins, and auxiliary factors such as arginine, CoQ10, Idebenone, L-carnitine, and creatine may be prescribed to improve the general function of the mitochondria. Often, a combination of medications may be used. Your healthcare provider can determine the best supplements and combinations to use for your specific condition. Even though these supplements are available over the counter, it is best to confer with a healthcare expert before experimenting with these medications. The effects have not been fully validated.

The National Ataxia Foundation has a list of medications used by individuals with Friedreich ataxia. This list can be found here: https://www.christopherreeve.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Medications-for-Ataxia.pdf

Health conditions that arise due to Friedreich ataxia are treated as appropriate for the individual. Diabetes, other pancreatic issues, heart disease, orthopedic conditions, and others are treated on an individual basis.

Rehabilitation Treatments

Care of individuals with Friedreich ataxia follow the Consensus Clinical Management Guidelines for Friedreich Ataxia, 2014, led by Louise A Corben, David Lynch, Massimo Pandolfo, Jorg B Schulz, Martin B Delatycki and the Clinical Management Guidelines writing group as published in the Journal Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, volume 9. The complete article is available here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4280001/

Treatments may include assistance with these issues:

Assistive Technologies vary in levels. Adaptive equipment for speaking, eating, moving, writing, and other activities of daily living (ADLs) that require adaptions for independence. Simple devices may include a built-up utensil for eating. More complicated devices can create speech for an individual with movement from their eyes or forehead muscles.

Ataxia is treated with exercises for balance, flexibility, coordination, and strengthening. Interventions for improvement of activities of daily living should be provided as well as monitoring for growth and development. Fall prevention education and safety should be provided. Assistive devices such as walkers and wheelchairs can enhance mobility especially for distances.

Bowel, bladder, and sexual issues usually appear in those at a longer point of duration of Friedreich ataxia or with late-onset development. This may include incoordination of bladder contraction and urinary sphincter opening, tone/spasticity in the bladder and bowel, and erectile (males) or lubrication (females) issues. Treatment of bowel and bladder issues includes the use of a regimented bowel program and intermittent catheterization to avoid incontinence. Sexual issues are generally treated with erectile medications and lubricants (both topical or oral).

Cardiomyopathy can be delayed with lifestyle modifications such as lower salt intake, avoiding alcohol, and not smoking. Medications can be used to lower blood pressure. Heart pacemakers or ablation procedures can be used as needed.

Diabetes is treated with diet and exercise. If diabetes progresses, medication can be used to control blood sugar in the body.

Eye movements are treated with strengthening of the eye muscles. Occasionally, glasses, contact lenses, and some medications have been beneficial. Surgery to balance eye muscles may be performed.

Fatigue can also affect functional abilities. Overall strengthening, assigned rest periods, and conservation of movement may improve fatigue. Assistive mobility devices enhance distance function.

Foot issues may include a high foot arch or club foot. These can be treated with orthotics such as braces to adjust or maintain alignment. In some cases, surgical intervention is needed.

Hearing aids may be required to improve hearing ability. As the hearing loss is from nerve dysfunction, hearing aids do not always alleviate the issue. Cochlear implants have been used for some individuals.

Oral motor issues of speaking and swallowing can be treated with exercises to help improve function. If feeding becomes unsafe due to poor swallowing or choking, a feeding tube may be placed through the skin of the abdomen into the stomach to ensure nutrition and fluids. This may be done as a supplement to oral intake or for all food and fluid.

Orthopedic conditions, especially scoliosis (curvature of the spine) can be treated by strengthening the trunk. If the muscle imbalance progresses, a body splint is used to assist with alignment. When severe, surgical correction is required. Flexible rods can be placed along the vertebrae of the spine using minimally invasive surgical techniques to provide stability with only a small amount of flexibility affected.

Osteoporosis can develop in any individual who does not bear weight. With Friedreich ataxia bone mineral production can be disturbed both metabolically within the body and due to nutritional issues. Bone density testing is important to ensure bones are getting the nutrients needed as well as maintaining bone strength. Treatments include standing or using a standing frame if needed and after bone density testing has demonstrated the bones have the strength needed to hold the body upright. Therapy and exercise can assist with maintaining bone density. Medication can strengthen weakened bones.

Pain can be caused by a variety of issues in Friedreich ataxia. Most often, pain is the result of cramped muscles or muscles with tone/spasticity. A combination of physical therapy and medication is used to ensure comfort.

Palliative Care is a health approach to providing comfort and optimizing quality of life for those with significant health issues. It is a process that can assist with end-of-life physical and emotional needs.

Peripheral Neuropathy can be caused when the nerves of the body are damaged leading to pain and numbness. It generally appears first in the hands and feet. It can be treated with skin creams to reduce pain and low-dose anticonvulsant medications. Stimulation through movement is also helpful to increase blood flow.

Proprioception is also treated with exercises to strengthen the core of the body, general exercises to improve overall strength, motor function, and balance, as well as sensory stimulation. Tai chi can be an additional therapy to boost proprioception, especially in the legs.

Quality of Life issues affect most individuals with Friedreich ataxia. Not being able to do things you once did or living with a chronic health condition can be challenging. Depression, anxiety, and psychosis have been related in some individuals with Friedreich ataxia. Having input from a qualified therapist can help you develop the skills needed to meet challenges.

Restless leg syndrome can be caused by contractions of the leg muscles when at rest or due to tone/spasticity. Therapeutic intervention can greatly assist in helping the muscles of the legs to relax. This might need to be supplemented with medication.

Sleep disturbances may occur from disordered breathing, pain, restless leg syndrome, or other health issues. Treating sleep disturbances should be approached by diagnosis and treatment of the underlying condition. A sleep study test can help determine if the disruption is from breathing issues which can be treated with ventilation support. Treatment of other health issues that may be affecting sleep should be made as needed.

Tone/spasticity can occur from message miscommunication in the nervous system. Gentle stretching and range of motion exercises can reduce tone/spasticity. Medications are available to help control muscle overtightening.

Weakness can be so confounding that it masks motor function. Therefore, strengthening may be used to improve muscle strength which will improve motor function.

History

A pathologist and neurologist named Nikolaus Friedreich first described this condition in the medical literature in 1863 after studying and following the progression in six cases. He was able to perform an autopsy on four of those individuals which led to his conclusion that the cause of the condition was axonal thinning of the nerves but without loss of the entire nerve. It was not until very late in his career (1876) that he recognized a genetic component to the condition. This coincided with studies of genetics in general. Friedreich’s work was based in Heidelberg, Germany.

French medical researchers did further work following Friedreich however, it was not until 120 years later that the actual genetic underpinnings of the disease were determined! This was not from a lack of study but was due to the inability to understand how to unlock genetic structures. The genetic connection was published by a group lead by Victoria Campuzano in 1996. This opened the possibility of treatments.

Clinical guidelines were produced in 2014. This greatly improves the care for individuals with Friedreich ataxia.

A cure for Friedreich ataxia is not known at this time. However, scientists and researchers are working toward this goal as well as to treat specific symptoms. Overall research includes aspects of determining the source of gene mutation and how to prevent it as well as understanding the frataxin process in the cell.

The study of pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) obtained from the skin or blood cells of the individual are being studied to understand the genetic process of how the FXN gene produces frataxin as well as replacing it in the body. Mitochondrial functions are also being examined for the process. Internal body biomarkers are being studied to look for changes in the body that can prevent the onset of additional health issues. A protein that can be delivered to the individual to replace frataxin in the mitochondria is also being studied.

Facts and Figures

Prevalence of Friedreich ataxia is one in 50,000 in the USA and one in 40,000 worldwide.

There are no gender differences in the development of Friedreich ataxia.

Friedreich ataxia is more prominent in individuals of European, Middle Eastern, South Asian, and North African descent.

Cardiomyopathy (enlarged heart) and cardiac arrhythmia are the most common causes of death.

Resources

If you are looking for more information about Friedreich ataxia or have a specific question, our Information Specialists are available business weekdays, Monday through Friday, toll-free at 800-539-7309 from7:00 am to12:00 am (midnight) EST.

Check out our repository of fact sheets on hundreds of topics ranging from state resources to secondary complications of paralysis. We encourage you to reach out to Friedreich ataxia support groups and organizations, including:

Friedreich’s Ataxia Parents Group (FAPG)

Friedreich’s Ataxia Research Alliance

National Organization of Rare Diseases (NORD)

Clinical Practice Guidelines for Friedreich ataxia can be found at these sites:

National Institutes of Health:

Orphan Journal of Rare Diseases

References

Alper G, Narayanan V. Friedreich’s Ataxia. Pediatr Neurol. 2003 May;28(5):335-41. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(03)00004-3. PMID: 12878293.

Amini O, Lakziyan R, Abavisani M, Sarchahi Z. The Cardiomyopathy of Friedreich’s Ataxia Common in a Family: A Case Report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021 May 24;66:102408. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102408. PMID: 34136207; PMCID: PMC8178102.

Aranca TV, Jones TM, Shaw JD, Staffetti JS, Ashizawa T, Kuo SH, Fogel BL, Wilmot GR, Perlman SL, Onyike CU, Ying SH, Zesiewicz TA. Emerging Therapies in Friedreich’s Ataxia. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2016;6(1):49-65. doi: 10.2217/nmt.15.73. PMID: 26782317; PMCID: PMC4768799.

Bhat MA, Dhaneshwar S. Neurodegenerative Disease: New Hopes and Perspectives. Curr Mol Med. 2023 Sep 7. doi: 10.2174/1566524023666230907093451. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37691199.

Boesch S, Indelicato E. Experimental Drugs for Friedreich’s Ataxia: Progress and Setbacks in Clinical Trials. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2023 Jul-Dec;32(11):967-969. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2023.2276758. Epub 2023 Nov 24. PMID: 37886821.

Brandes MS, Gray NE. NRF2 as a Therapeutic Target in Neurodegenerative Diseases. ASN Neuro. 2020 Jan-Dec;12:1759091419899782. doi: 10.1177/1759091419899782. PMID: 31964153; PMCID: PMC6977098.

Campuzano, Victoria, et al. Friedreich’s Ataxia: Autosomal Recessive Disease Caused by an Intronic GAA Triplet Repeat Expansion. Science 271.5254 (1996): 1423-1427.

Cook A, Giunti P. Friedreich’s Ataxia: Clinical Features, Pathogenesis and Management. Br Med Bull. 2017 Dec 1;124(1):19-30. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldx034. PMID: 29053830; PMCID: PMC5862303.

Corben LA, Lynch D, Pandolfo M, Schulz JB, Delatycki MB, Clinical Management Guidelines Writing Group. Consensus Clinical Management Guidelines for Friedreich Ataxia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014 Nov 30;9:184. doi: 10.1186/s13023-014-0184-7. PMID: 25928624; PMCID: PMC4280001.

Delatycki MB, Bidichandani SI. Friedreich ataxia–Pathogenesis and Implications for Therapies. Neurobiol Dis. 2019 Dec;132:104606. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104606. Epub 2019 Sep 5. PMID: 31494282.

Dorn GW 2nd, Dang X. Predicting Mitochondrial Dynamic Behavior in Genetically Defined Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells. 2022 Mar 19;11(6):1049. doi: 10.3390/cells11061049. PMID: 35326500; PMCID: PMC8947719.

Dunn J, Tamaroff J, DeDio A, Nguyen S, Wade K, Cilenti N, Weber DR, Lynch DR, McCormack SE. Bone Mineral Density and Current Bone Health Screening Practices in Friedreich’s Ataxia. Front Neurosci. 2022 Mar 14;16:818750. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.818750. PMID: 35368287; PMCID: PMC8964400.

Fahey MC, Corben L, Collins V, Churchyard AJ, Delatycki MB. How is Disease Progress in Friedreich’s Ataxia Best Measured? A Study of Four Rating Scales. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007 Apr;78(4):411-3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.096008. Epub 2006 Oct 20. PMID: 17056635; PMCID: PMC2077798.

Grubman A, White AR, Liddell JR. Mitochondrial Metals as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Neurodegeneration. Br J Pharmacol. 2014 Apr;171(8):2159-73. doi: 10.1111/bph.12513. PMID: 24206195; PMCID: PMC3976628.

Hohenfeld C, Terstiege U, Dogan I, Giunti P, Parkinson MH, Mariotti C, Nanetti L, Fichera M, Durr A, Ewenczyk C, Boesch S, Nachbauer W, Klopstock T, Stendel C, Rodríguez de Rivera Garrido FJ, Schöls L, Hayer SN, Klockgether T, Giordano I, Didszun C, Rai M, Pandolfo M, Rauhut H, Schulz JB, Reetz K. Prediction of the Disease Course in Friedreich Ataxia. Sci Rep. 2022 Nov 10;12(1):19173. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-23666-z. PMID: 36357508; PMCID: PMC9649725.

Holmström KM, Kostov RV, Dinkova-Kostova AT. The Multifaceted Role of Nrf2 in Mitochondrial Function. Curr Opin Toxicol. 2016 Dec;1:80-91. doi: 10.1016/j.cotox.2016.10.002. PMID: 28066829; PMCID: PMC5193490.

Indelicato E, Nachbauer W, Eigentler A, Amprosi M, Matteucci Gothe R, Giunti P, Mariotti C, Arpa J, Durr A, Klopstock T, Schöls L, Giordano I, Bürk K, Pandolfo M, Didszdun C, Schulz JB, Boesch S; EFACTS (European Friedreich’s Ataxia Consortium for Translational Studies). Onset Features and Time to Diagnosis in Friedreich’s Ataxia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020 Aug 3;15(1):198. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01475-9. PMID: 32746884; PMCID: PMC7397644.

Keita M, McIntyre K, Rodden LN, Schadt K, Lynch DR. Friedreich Ataxia: Clinical Features and New Developments. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2022 Oct;12(5):267-283. doi: 10.2217/nmt-2022-0011. Epub 2022 Jun 29. PMID: 35766110; PMCID: PMC9517959.

Kilikevicius A, Wang J, Shen X, Rigo F, Prakash TP, Napierala M, Corey DR. Difficulties Translating Antisense-Mediated Activation of Frataxin Expression from Cell Culture to Mice. RNA Biol. 2022;19(1):364-372. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2022.2043650. Epub 2021 Dec 31. PMID: 35289725; PMCID: PMC8928816.

Koeppen AH. Nikolaus Friedreich and Degenerative Atrophy of the Dorsal Columns of the Spinal Cord. J Neurochem. 2013 Aug;126 Suppl 1(0 1):4-10. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12218. Erratum in: J Neurochem. 2013 Aug;126 Suppl 1:155. PMID: 23859337; PMCID: PMC3721437.

Lubozynski MF, Roelofs RI. Friedreich’s Ataxia. South Med J. 1975 Jun;68(6):757-63. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197506000-00026. PMID: 166449.

Lynch DR, Johnson J. Omaveloxolone: Potential New Agent for Friedreich Ataxia. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2021;11(2):91-98.

Lynch DR, Chin MP, Delatycki MB, Subramony SH, Corti M, Hoyle JC, Boesch S, Nachbauer W, Mariotti C, Mathews KD, Giunti P, Wilmot G, Zesiewicz T, Perlman S, Goldsberry A, O’Grady M, Meyer CJ. Safety and Efficacy of Omaveloxolone in Friedreich Ataxia (MOXIe Study). Ann Neurol. 2021;89(2):212-225.

Lynch DR, Farmer J, Hauser L, Blair IA, Wang QQ, Mesaros C, Snyder N, Boesch S, Chin M, Delatycki MB, Giunti P, Goldsberry A, Hoyle C, McBride MG, Nachbauer W, O’Grady M, Perlman S, Subramony SH, Wilmot GR, Zesiewicz T, Meyer C. Safety, Pharmacodynamics, and Potential Benefit of Omaveloxolone in Friedreich Ataxia. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;6(1):15-26.

Marmolino D. Friedreich’s Ataxia: Past, Present and Future. Brain Res Rev. 2011 Jun 24;67(1-2):311-30. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2011.04.001. Epub 2011 Apr 17. PMID: 21550666.

Ocana-Santero G, Díaz-Nido J, Herranz-Martín S. Future Prospects of Gene Therapy for Friedreich’s Ataxia. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Feb 11;22(4):1815. doi: 10.3390/ijms22041815. PMID: 33670433; PMCID: PMC7918362.

Oender D, Faber J, Wilke C, Schaprian T, Lakghomi A, Mengel D, Schöls L, Traschütz A, Fleszar Z, Dufke C, Vielhaber S, Machts J, Giordano I, Grobe-Einsler M, Klopstock T, Stendel C, Boesch S, Nachbauer W, Timmann-Braun D, Thieme AG, Kamm C, Dudesek A, Tallaksen C, Wedding I, Filla A, Schmid M, Synofzik M, Klockgether T. Evolution of Clinical Outcome Measures and Biomarkers in Sporadic Adult-Onset Degenerative Ataxia. Mov Disord. 2023 Apr;38(4):654-664. doi: 10.1002/mds.29324. Epub 2023 Jan 25. PMID: 36695111.

Pandolfo M. Friedreich’s Ataxia: Clinical Aspects and Pathogenesis. Semin Neurol. 1999;19(3):311-21. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040847. PMID: 12194387.

Parkinson MH, Boesch S, Nachbauer W, Mariotti C, Giunti P. Clinical Features of Friedreich’s Ataxia: Classical and Atypical Phenotypes. J Neurochem. 2013 Aug;126 Suppl 1:103-17. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12317. PMID: 23859346.

Pilch J, Jamroz E, Marszał E. Friedreich’s Ataxia. J Child Neurol. 2002 May;17(5):315-9. doi: 10.1177/088307380201700501. PMID: 12150575.

Portaro S, Russo M, Bramanti A, Leo A, Billeri L, Manuli A, La Rosa G, Naro A, Calabrò RS. The Role of Robotic Gait Training and tDCS in Friedreich Ataxia Rehabilitation: A Case Report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Feb;98(8):e14447. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014447. PMID: 30813143; PMCID: PMC6407999.

Pousset F, Kalotka H, Durr A, Isnard R, Lechat P, Le Heuzey JY, Thomas D, Komajda M. Parasympathetic Activity in Friedreich’s Ataxia. Am J Cardiol. 1996 Oct 1;78(7):847-50. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89245-4. PMID: 8857499.

Reddy PH. Role of Mitochondria in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Mitochondria as a Therapeutic Target in Alzheimer’s Disease. CNS Spectr. 2009 Aug;14(8 Suppl 7):8-13; discussion 16-8. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900024901. PMID: 19890241; PMCID: PMC3056539.

Reetz K, Dogan I, Hilgers RD, Giunti P, Parkinson MH, Mariotti C, Nanetti L, Durr A, Ewenczyk C, Boesch S, Nachbauer W, Klopstock T, Stendel C, Rodríguez de Rivera Garrido FJ, Rummey C, Schöls L, Hayer SN, Klockgether T, Giordano I, Didszun C, Rai M, Pandolfo M, Schulz JB; EFACTS study group. Progression Characteristics of the European Friedreich’s Ataxia Consortium for Translational Studies (EFACTS): A 4-year Cohort Study. Lancet Neurol. 2021 May;20(5):362-372. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00027-2. Epub 2021 Mar 23. PMID: 33770527.

Salazar P, Indorkar R, Dietrich M, Farzaneh-Far A. Cardiomyopathy in Friedreich’s Ataxia. Eur Heart J. 2018 Feb 14;39(7):631. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx607. PMID: 29059291.

Stepanova A, Magrané J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurons in Friedreich’s Ataxia. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2020 Jan;102:103419. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2019.103419. Epub 2019 Nov 23. PMID: 31770591.

Tonon C, Lodi R. Idebenone in Friedreich’s Ataxia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008 Sep;9(13):2327-37. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.13.2327. PMID: 18710357.

Urrutia PJ, Mena NP, Núñez MT. The Interplay Between Iron Accumulation, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Inflammation During the Execution Step of Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front Pharmacol. 2014 Mar 10;5:38. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00038. PMID: 24653700; PMCID: PMC3948003.

Waldvogel D, van Gelderen P, Hallett M. Increased Iron in the Dentate Nucleus of Patients with Friedreich’s Ataxia. Ann Neurol. 1999 Jul;46(1):123-5. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199907)46:1<123::aid-ana19>3.0.co;2-h. PMID: 10401790.

Weidemann F, Störk S, Liu D, Hu K, Herrmann S, Ertl G, Niemann M. Cardiomyopathy of Friedreich Ataxia. J Neurochem. 2013 Aug;126 Suppl 1:88-93. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12217. PMID: 23859344.

Weidemann F, Scholz F, Florescu C, Liu D, Hu K, Herrmann S, Ertl G, Störk S. Herzbeteiligung bei Friedreich-Ataxie [Heart Involvement in Friedreich’s Ataxia]. Herz. 2015 Mar;40 Suppl 1:85-90. German. doi: 10.1007/s00059-014-4097-y. Epub 2014 May 23. PMID: 24848865.

Wood NW. Diagnosing Friedreich’s Ataxia. Arch Dis Child. 1998 Mar;78(3):204-7. doi: 10.1136/adc.78.3.204. PMID: 9613347; PMCID: PMC1717493.

Zhang S, Napierala M, Napierala JS. Therapeutic Prospects for Friedreich’s Ataxia. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019 Apr;40(4):229-233. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2019.02.001. PMID: 30905359; PMCID: PMC6826337.

Zighan M, Arkadir D, Douiev L, Keller G, Miller C, Saada A. Variable Effects of Omaveloxolone (RTA408) on Primary Fibroblasts with Mitochondrial Defects. Front Mol Biosci. 2022 Aug 12;9:890653. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.890653. PMID: 36032663; PMCID: PMC9411646.