Neurofibromatosis

Neurofibromatosis (NF) is a genetic disorder that causes multiple tumors (lesions) in the nervous system and skin. These tumors can appear in the central nervous system (CNS) which includes the brain and spinal cord, and in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) which includes all the other nerves in the body (nerves in internal organs, bones, muscles, and skin). As nerves are throughout the entire body, these tumors can appear anywhere. The tumors are most often benign (non-cancerous) but in some forms of disease, cases can be cancerous.

In neurofibromatosis, neurological symptoms can occur. This can lead to concerns with movement, behavior, cognitive function, and cardiovascular and musculoskeletal issues.

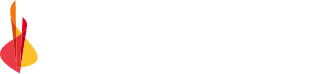

Neurofibromatosis appears in individuals regardless of gender, race, or ethnicity.

There are three types of neurofibromatosis (NF). Each type has different causes and symptoms, but all include tumors of the nerves.

- Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1), also known as von Recklinghausen’s disease, is the most common form (96% of cases). Peripheral nerve tumors which are called neurofibromas, cause skin changes and bone deformations. NF1 is usually diagnosed in children.

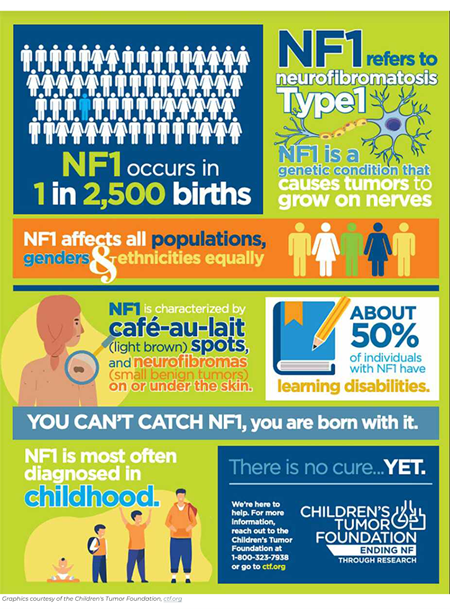

- Neurofibromatosis 2 or NF2 (3% of cases) is characterized by tumors created by Schwann cells which are glial cells that surround neurons in the PNS. This leads to hearing loss and vestibular issues (balance, dizziness, vertigo) due to tumors on the eighth cranial nerve located in the head. NF2 is usually limited to the nervous system with only occasional skin tumors. NF2 is usually diagnosed in teens or young adults.

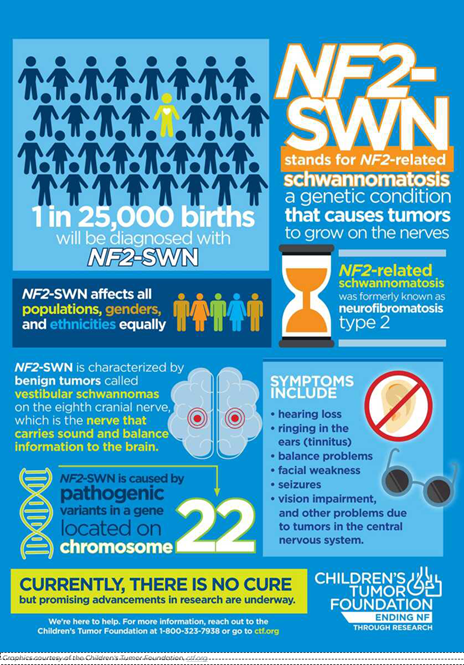

- Schwannomatosis or SWN (<1% of cases) is an uncontrollable growth of Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system that creates the protective coating of nerve cells called myelin). This condition leads to chronic pain and movement issues. At least two schwannomas must be present for the diagnosis. This condition usually occurs in individuals over 20-30 years. A genetic family history may be present, but more often, it is not.

Note: In 2022, an international consensus recommended combining neurofibromatosis type 2 and schwannomatosis into one category. This is due to overlapping types of tumors and phenotypes (similar characteristics). Genetic work continues to refine this combined category.

Neurofibromatosis is genetic, passing from parent to child. However, some cases develop by spontaneous mutation in the genetic structure of individuals. An individual that either inherits or develops a spontaneous case of neurofibromatosis, can pass it genetically to their children.

The genetics of neurofibromatosis is due to ineffective tumor suppression genes within the DNA of cells. The affected tumor suppression gene is different depending on the type of neurofibromatosis. Tumors can develop on the nerves and in the skin because the tumor suppression gene does not produce the effects needed to prevent overgrowth. Since the gene is not stopping tumor production, tumors can appear anywhere in the body.

The chromosomal location of neurofibromatosis genetic effects is indicated in the following table:

| Type | Location | Effect |

| NF1 | Chromosome 17q11.2 | Neurofibromin (a tumor suppression protein) negatively affects Ras/MAPK and P13/mTOR signaling pathways |

| NF2 | Chromosome 22q12 | Merlin (a tumor suppression protein) related to ezrin-radixin-moesin affects the modulation or control of P13K/AKT, Raf/MEK/ERK, and mTOR signaling pathways. |

| SWN | Unclear | Tumor suppression genes SMARCB1 and LZTR1have inactivating mutations |

Symptoms/Diagnosis

Symptoms of neurofibromatosis can be a challenge to pinpoint. The symptoms may include many characteristics of other health issues. The diagnosis of neurofibromatosis is made when the symptoms are put together. Genetic testing is required for a definitive diagnosis. A known family history of neurofibromatosis helps lead to the diagnosis.

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1)

The criteria for diagnosing NF1 include the following:

- Light brown spots on the skin (café au lait)

- Six or more spots

- Children-five millimeters in diameter: adults-15 millimeters

- Most common indication of NF1 but not a conclusive symptom as these spots can occur in other diseases

- Cutaneous neurofibromas (bumps on the skin)/Nodular neurofibromas

- Two or more bumps

- May be present at birth but not yet risen to beneath the surface of the skin

- Commonly first seen in adolescence

- Usually pea-sized

- Soft in composition

- Not malignant

- Plexiform neurofibroma (one larger neurofibroma) that involve many nerves

- Occurs in the peripheral nervous system, outside of the brain or spinal cord

- Usually present at birth but not noticeable until older

- About 10% can become malignant (Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors, MPNSTs)

- Freckling in the armpit or groin

- Smaller than café au lait spots

- Appears by age 3-5

- Only a concern if other symptoms of NF1 are present

- Lisch nodules or iris hamartomas in the iris of the eyes (growths in the iris of the eyes)

- Not seen until adolescence

- Do not affect vision

- May not require treatment

- Optic pathway glioma (tumor of the optic nerve)

- Occurs by age six, rare in teens, extremely rare in adults

- Usually, non-symptomatic

- Can affect vision

- Malignant glioma can occur but does so rarely and usually in adults

- Bone deformities

- Poor eye socket formation

- Bowing of the tibia (shin bone) in the leg

- Pseudo arthritis

- Shorter height

- Larger heads

- Scoliosis

- Kyphosis

- Osteoporosis

- Relative with neurofibromatosis type 1

Other conditions found with NF1 can include:

- Blindness

- Glaucoma

- Cardiovascular Issues

- High blood pressure

- Renal (kidney) artery stenosis

- Aneurysm

- Congenital heart defects

- Damaged blood vessels

- Narrowing of the blood vessels

- Stroke

- Cognitive Issues

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Challenges focusing

- Memory issues

- Learning disabilities

- Social skill challenges

- Gastrointestinal tumors

- Neuroendocrine Tumors

- Neurological Concerns

- Headaches

- Pain

- Seizures

- Numbness/weakness/tingling

- Psychological Issues

- Anxiety

- Social skill challenges

- Isolation

- Depression

- Low self-esteem

- Embarrassment

- Cancer fears

- Visual special issues

- Early breast cancer in women

Neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2)

The diagnosis of NF2 is:

- Bilateral vestibular schwannomas (also known as acoustic neuroma)

Presumptive diagnosis includes:

- Family history of NF2

- Unilateral vestibular schwannoma and two of the following:

- Meningioma

- Glioma

- Schwannoma

- Juvenile posterior subcapsular lenticular opacity (in the lens of the eye)

- Juvenile cortical cataract

Symptoms of NF2 may include some or all of the following:

- Slow-growing tumors in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord,) the peripheral nervous system (all the nerves in the body,) or the meninges (the covering of the brain and spinal cord).

- Schwannomas (tumors of nerves protective barrier, myelin)

- Most often occurs at each branch of the eighth cranial nerve, on either or both sides of the body.

- The acoustic branch of the eighth cranial nerve which affects hearing.

- The vestibular branch of the eighth cranial nerve which affects position and balance.

- Schwannomas can occur just under the skin appearing as a bump.

- Schwannomas are usually benign but may need treatment or rarely can become malignant.

- Meningioma (tumors of the tissue protecting the brain and spinal cord)

- Can develop multiple tumors next to the brain and spinal cord

- Ependymoma (occurs within the spinal cord)

- Usually are benign

- Typically, is asymptomatic

- Diagnosis in children is first noticed with visual concerns and meningiomas.

- Diagnosis in teens and adults is first noticed with hearing and balance issues.

- Issues for NF2 diagnosis:

- Schwannomas in the skin

- Visual impairment

- Seizures

- Weakness from spinal cord tumors

- Hearing loss or ringing in the ears

- Balance issues

- Schwannomas (tumors of nerves protective barrier, myelin)

Schwannomatosis

Multiple benign tumors of Schwann cells with uncontrolled growth are known as Schwannomatosis.

Individuals may have tumors in only one part of the body or at one level of the spinal cord, others may have tumors in various parts of the body. Symptoms occur just where the tumors are located. Occasionally, the individual has no symptoms.

Diagnostic criteria for Schwannomatosis includes:

- Two schwannomas in areas other than the skin with one confirmed by biopsy.

- Bilateral vestibular schwannomas or identical NF2 tumors in two different areas of the body (schwannoma, meningioma, ependymoma) or two NF2-related schwannomatosis.

- Pain, numbness or weakness, and muscle loss.

Symptoms specific to schwannomatosis include:

- Chronic pain

- Headaches

- Numbness, tingling, or weakness in the extremities

- Bowel and/or bladder dysfunction

- Facial weakness

- Vision changes

- Lumps under the skin

- Usually diagnosed in individuals over the age of 30 years

- NF2 has been ruled out

Diagnosis of neurofibromatosis of any type can begin before conception with genetic testing of each parent to establish if they carry or have the genetic mutation that will produce neurofibromatosis. Some parents have genetic testing performed after pregnancy occurs.

History and physical examination You or your child’s healthcare professional will ask about any genetic diseases in your family’s history. They will perform a complete physical examination and neurological examination. They will ask you about the onset of the health concerns, the intensity of the issue, and what you have been doing at home to help yourself or your child.

Genetic testing of the individual with neurofibromatosis to confirm the genetic change.

Imaging studies such as a CT scan, MRI, or PET scan may be performed to assess for tumors within the body.

A biopsy may be performed to confirm the tumor type.

Hearing and vision testing are performed as needed.

Diagnosis may be made from the symptoms presented as listed above.

Treatments

Neurofibromatosis treatment is based on the subset of the disease.

Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) usually does not require treatment, especially if mild. On occasion, tumors can grow large or rarely become malignant which may require chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery. A combination of these treatments may be needed.

Cutaneous neurofibromas are usually left alone. Some individuals have used some of these treatments with varying results:

- Cutaneous neurofibromas are usually treated with surgical removal if larger than 4 cm. These are typically removed singly, not in large groups.

- Multiple cutaneous neurofibromas have been removed by laser. CO2 laser therapy has been used to treat multiple skin tumors but does have side effects of scarring and changes in pigmentation.

- Biopsy equipment can be utilized to remove neurofibromas of about 10 small tumors at one time.

- Electrodessication can be used to remove over 100 very small tumors at one time.

- Radiofrequency ablation has been performed with some success.

Plexiform neurofibromas may be removed if they are in an area where surgery can be safely performed.

- Surgery, including radiotherapy of beams of gamma rays, is the primary treatment if the plexiform neurofibroma needs to be removed.

- Monitoring may be used for difficult-to-remove tumors.

- Chemotherapy and radiation may be used for malignant plexiform neurofibromas.

- The medication Koselugo (selumetinib) is being used for children with NF1 for plexiform tumors especially if the tumor is inoperable.

Tumors will regrow about 20% of the time after a complete removal. Fifty percent of tumors cannot be completely removed.

Specialists in medicine, education, or mental health treat other medical issues.

Neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2)

Treatment of NF2 is provided by symptoms.

- Therapy is used to improve balance and other mobility issues.

- Alternative means of communication through augmentative communication devices or sign language are used to help communication.

- Cochlear implants are often used to assist with hearing.

- Peripheral nerve, spinal, and brain tumors are treated with surgery if the tumor can be surgically reached. If the tumor is in a difficult position, radiotherapy using gamma rays can be used.

- Chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery may be utilized for malignant tumors.

- The drug bevacizumab has been used off-label for tumor treatment, especially for glioblastoma tumors.

Schwannomatosis treatment consists of the management of symptoms. Individuals are carefully managed with treatments for pain control and movement-enhancing equipment. Surgery is performed if the tumor is affecting body functions such as weakness, visual changes, bowel and bladder issues, and pain.

Clinical trials are being conducted to improve the life and treatment of individuals with neurofibromatosis. Studies about brain issues are being carried out in those with NR1 to create early interventions for cognitive development. NF2 studies include factors that may reduce the growth of tumors.

Drug-related studies include blocking the enzyme mitogen-activated protein kinase in NF1, chemotherapy drugs for NF2-related schwannomas, and a virus to eliminate tumor cells in schwannomatosis.

More information about new and continuing studies can be found at https://clinicaltrials.gov/. Even if a trial is not in your area, or you want more information about clinical trials for neurofibromatosis, information about the trials will provide you with discussion points for your healthcare professional.

Rehabilitation Therapies

Finding a specialist in neurofibromatosis can be difficult. Academic medical centers are a place to either initiate and follow care or to assist in finding a specialist in your community. Locate a specialist who can refer or coordinate care with a health professional in your community. Children will require pediatric care; adults should seek treatment from adult specialists.

It will be critical for teens to participate in the transition of care programs to move from pediatric treatment to adult treatment. Moving from pediatric care involves ensuring the teen understands their issues and concerns, meeting the adult care team, and learning skills to advocate for their care needs.

Neurofibromatosis has many health concerns. Each health issue should be treated by specialists specific to that issue. A team of specialists may be needed. It is often beneficial to select one healthcare professional as the leader of your team to reduce conflicting information and coordinate care.

A neurologist will provide neurological evaluation and treatment. The specialist will be by patient age, either specializing in adults or pediatrics with transitioning as the individual ages.

An internal medicine specialist can assist with day-to-day healthcare issues from concerns that affect everyone to health issues specific to those with neurofibromatosis.

A pediatrician is needed for day-to-day issues of children.

A neurosurgeon may be needed if tumors need to be removed due to size, pain, or body function effects.

A neuro-oncologist may be consulted if there is concern about tumor status, benign or malignant.

Radiologists may assist with imaging of the neurofibromas or anatomical effects of the tumor on body function.

Dermatologists can assist with skin issues, lesions, and possible removal of tumors if they can be safely treated.

A physiatrist is a physician who will greatly assist with providing long-term care for mobility, activities of daily living, and chronic issues.

Genetic counselors are critical to planning pregnancies and other health issues that appear or should be monitored.

Ophthalmologists are needed to treat and monitor eye and vision issues especially if the optic nerve is affected.

Audiologists treat long-term hearing issues.

Orthopedic surgeons provide care for bone growth issues, prevention of changes in bone development, and surgical correction if needed.

Pain specialists help treat chronic pain effectively.

Ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialists can aid in improving hearing, breathing, and swallowing.

Family counselors provide strategies to assist with navigating the world for individuals with neurofibromatosis and their families to gain strategies to deal with ongoing mental wellness issues.

Educators and Teachers should be included in an Independent Education Plan specific to the needs of children with neurofibromatosis to ensure their education is tailored to the child’s needs.

Physical and Occupational Therapists will provide treatment and equipment suggestions and strategies to improve function and mobility.

History

Around the world, neurofibromatosis has been described by ancient cultures. In Egypt, it was recorded on papyrus scrolls around 1500 B.C., represented in a statue in Smyrna in 323 B.C., and depicted on coins by Parthian Kings in 247 B.C. In the 13th century, it was included in Monk’s drawings. NF1 was found in an Inca mummy around 1500.

Eduard Sandifort described acoustic neuroma in 1777 with John H. Wishart identifying NF2 in 1822. In 1882, Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen reported NF1 cases and identified neurofibromas. Schwannomatosis was described in 1849. In the 1970s, NF2 was noted to be a hereditary condition. In 1990, schwannomatosis was described as a form of neurofibromatosis.

Since these early times, much effort has been directed at developing better classification schemes that provide direction for researchers and scientists to develop strategies for treatments, therapies, and movement toward genetic repair. A better understanding of genetics in the 1990s and 2000s has propelled treatments.

Understanding of neurofibromatosis has exploded in today’s research environment. The treatment of large numbers of mast cells in the neurofibromas, bone density, inappropriate bone signaling, and indications for benign tumors to become malignant are just a few of the many advancements in recent years.

Treatments for outcomes of neurofibromatosis such as attention deficit disorders and cosmetic procedures have also excelled in research. Diagnosis of bone issues, freckling, and mortality are also being studied. MicroRNA has been under study as a biomarker to indicate the progress of the disease as well as an entry to new treatment ideas.

Facts and Figures

NF occurs in one of every 2,500 to 3,000 people.

NF1 and NF2 have a 50% rate of occurrence in a child if one parent has NF. Of those who have NF1, 30 to 50% developed spontaneously.

Schwannomatosis occurs in one in 40,000 people.

Resources

If you are looking for more information on neurofibromatosis or have a specific question, our Information Specialists are available business weekdays, Monday through Friday, toll-free at 800-539-7309 from 7:00 a.m. to 12:00 a.m. (midnight) EST.

Additionally, the Reeve Foundation maintains fact sheets with additional resources. Check out our repository of fact sheets on hundreds of topics ranging from state resources to secondary complications of paralysis.

We encourage you to reach out to organizations, including associations that feature news, research support, resources, national networks of support groups, clinics, and specialty hospitals.

Community Resources

Children’s Tumor Foundation https://www.ctf.org/

National Institutes of Health, Rare Diseases https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/10420/neurofibromatosis

Neurofibromatosis Network https://nfnetwork.org/

References

Anderson MK, Johnson M, Thornburg L, Halford Z. A Review of Selumetinib in the Treatment of Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Related Plexiform Neurofibromas. Ann Pharmacother. 2022 Jun;56(6):716-726. doi: 10.1177/10600280211046298. Epub 2021 Sep 18. PMID: 34541874.

Armstrong AE, Belzberg AJ, Crawford JR, Hirbe AC, Wang ZJ. Treatment Decisions and the Use of MEK Inhibitors for Children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Related Plexiform Neurofibromas. BMC Cancer. 2023 Jun 16;23(1):553. doi: 10.1186/s12885-023-10996-y. PMID: 37328781; PMCID: PMC10273716.

Asthagiri AR, Parry DM, Butman JA, Kim HJ, Tsilou ET, Zhuang Z, Lonser RR. Neurofibromatosis Type 2. Lancet. 2009 Jun 6;373(9679):1974-86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60259-2. Epub 2009 May 22. PMID: 19476995; PMCID: PMC4748851.

Brown R. Management of Central and Peripheral Nervous System Tumors in Patients with Neurofibromatosis. Curr Oncol Rep. 2023 Dec;25(12):1409-1417. doi: 10.1007/s11912-023-01451-z. Epub 2023 Oct 31. PMID: 37906356.

Coy S, Rashid R, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Santagata S. An Update on the CNS Manifestations of Neurofibromatosis Type 2. Acta Neuropathol. 2020 Apr;139(4):643-665. doi: 10.1007/s00401-019-02029-5. Epub 2019 Jun 4. Erratum in: Acta Neuropathol. 2020 Apr;139(4):667. doi: 10.1007/s00401-019-02044-6. PMID: 31161239; PMCID: PMC7038792.

Dhamija R, Plotkin S, Gomes A, Babovic-Vuksanovic D. LZTR1- and SMARCB1-Related Schwannomatosis. 2018 Mar 8 [updated 2024 Apr 25]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2024. PMID: 29517885.

Dombi E, Baldwin A, Marcus LJ, Fisher MJ, Weiss B, Kim A, Whitcomb P, Martin S, Aschbacher-Smith LE, Rizvi TA, Wu J, Ershler R, Wolters P, Therrien J, Glod J, Belasco JB, Schorry E, Brofferio A, Starosta AJ, Gillespie A, Doyle AL, Ratner N, Widemann BC. Activity of Selumetinib in Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Related Plexiform Neurofibromas. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 29;375(26):2550-2560. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1605943. PMID: 28029918; PMCID: PMC5508592.

Evans DG, Sainio M, Baser ME. Neurofibromatosis Type 2. J Med Genet. 2000 Dec;37(12):897-904. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.12.897. Erratum in: J Med Genet 2001 Oct;38(10):727a. PMID: 11106352; PMCID: PMC1734496.

Evans DG. NF2-Related Schwannomatosis. 1998 Oct 14 [updated 2023 Apr 20]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2024. PMID: 20301380.

Farschtschi S, Mautner VF, McLean ACL, Schulz A, Friedrich RE, Rosahl SK. The Neurofibromatoses. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020 May 15;117(20):354-360. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0354. PMID: 32657748; PMCID: PMC7373809.

Goetsch Weisman A, Weiss McQuaid S, Radtke HB, Stoll J, Brown B, Gomes A. Neurofibromatosis- and Schwannomatosis-Associated Tumors: Approaches to Genetic Testing and Counseling Considerations. Am J Med Genet A. 2023 Oct;191(10):2467-2481. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.63346. Epub 2023 Jul 24. PMID: 37485904.

Goldbrunner R, Weller M, Regis J, Lund-Johansen M, Stavrinou P, Reuss D, Evans DG, Lefranc F, Sallabanda K, Falini A, Axon P, Sterkers O, Fariselli L, Wick W, Tonn JC. EANO Guideline on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Vestibular Schwannoma. Neuro Oncol. 2020 Jan 11;22(1):31-45. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noz153. PMID: 31504802; PMCID: PMC6954440.

Gross AM, Glassberg B, Wolters PL, Dombi E, Baldwin A, Fisher MJ, Kim A, Bornhorst M, Weiss BD, Blakeley JO, Whitcomb P, Paul SM, Steinberg SM, Venzon DJ, Martin S, Carbonell A, Heisey K, Therrien J, Kapustina O, Dufek A, Derdak J, Smith MA, Widemann BC. Selumetinib in Children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 and Asymptomatic Inoperable Plexiform Neurofibroma at Risk for Developing Tumor-Related Morbidity. Neuro Oncol. 2022 Nov 2;24(11):1978-1988. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noac109. PMID: 35467749; PMCID: PMC9629448.

Gross AM, Wolters PL, Dombi E, Baldwin A, Whitcomb P, Fisher MJ, Weiss B, Kim A, Bornhorst M, Shah AC, Martin S, Roderick MC, Pichard DC, Carbonell A, Paul SM, Therrien J, Kapustina O, Heisey K, Clapp DW, Zhang C, Peer CJ, Figg WD, Smith M, Glod J, Blakeley JO, Steinberg SM, Venzon DJ, Doyle LA, Widemann BC. Selumetinib in Children with Inoperable Plexiform Neurofibromas. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 9;382(15):1430-1442. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912735. Epub 2020 Mar 18. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2020 Sep 24;383(13):1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMx200013. PMID: 32187457; PMCID: PMC7305659.

Hirbe AC, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis Type 1: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Care. Lancet Neurol. 2014 Aug;13(8):834-43. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70063-8. PMID: 25030515.

Jiramongkolchai P, Schwartz MS, Friedman RA. Management of Neurofibromatosis Type 2-Associated Vestibular Schwannomas. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2023 Jun;56(3):533-541. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2023.02.012. Epub 2023 Mar 22. PMID: 36964092.

Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Cooper DN. Challenges in the Diagnosis of Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) in Young Children Facilitated by Means of Revised Diagnostic Criteria Including Genetic Testing for Pathogenic NF1 Gene Variants. Hum Genet. 2022 Feb;141(2):177-191. doi: 10.1007/s00439-021-02410-z. Epub 2021 Dec 20. PMID: 34928431; PMCID: PMC8807470.

Koontz NA, Wiens AL, Agarwal A, Hingtgen CM, Emerson RE, Mosier KM. Schwannomatosis: The Overlooked Neurofibromatosis? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013 Jun;200(6):W646-53. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8577. PMID: 23701098.

Korf BR. Neurofibromatosis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;111:333-40. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52891-9.00039-7. PMID: 23622184.

Ly KI, Blakeley JO. The Diagnosis and Management of Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Med Clin North Am. 2019 Nov;103(6):1035-1054. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2019.07.004. PMID: 31582003.

Miller DT, Freedenberg D, Schorry E, Ullrich NJ, Viskochil D, Korf BR; Council on Genetics; American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Health Supervision for Children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Pediatrics. 2019 May;143(5):e20190660. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0660. PMID: 31010905.

Mindrup R, Idoate R. Neurofibromatosis and a Portrait of 1 in 3000. AMA J Ethics. 2020 Jun 1;22(6):E513-524. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2020.513. PMID: 32580827.

Miraglia E, Moliterni E, Iacovino C, Roberti V, Laghi A, Moramarco A, Giustini S. Cutaneous Manifestations in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Clin Ter. 2020 Sep-Oct;171(5):e371-e377. doi: 10.7417/CT.2020.2242. PMID: 32901776.

Paganini I, Chang VY, Capone GL, Vitte J, Benelli M, Barbetti L, Sestini R, Trevisson E, Hulsebos TJ, Giovannini M, Nelson SF, Papi L. Expanding the Mutational Spectrum of LZTR1 in Schwannomatosis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015 Jul;23(7):963-8. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.220. Epub 2014 Oct 22. PMID: 25335493; PMCID: PMC4463507.

Perez-Becerril C, Evans DG, Smith MJ. Pathogenic Noncoding Variants in the Neurofibromatosis and Schwannomatosis Predisposition Genes. Hum Mutat. 2021 Oct;42(10):1187-1207. doi: 10.1002/humu.24261. Epub 2021 Jul 29. PMID: 34273915.

Plotkin SR, Messiaen L, Legius E, Pancza P, Avery RA, Blakeley JO, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Ferner R, Fisher MJ, Friedman JM, Giovannini M, Gutmann DH, Hanemann CO, Kalamarides M, Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Korf BR, Mautner VF, MacCollin M, Papi L, Rauen KA, Riccardi V, Schorry E, Smith MJ, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Stevenson DA, Ullrich NJ, Viskochil D, Wimmer K, Yohay K; International Consensus Group on Neurofibromatosis Diagnostic Criteria (I-NF-DC); Huson SM, Wolkenstein P, Evans DG. Updated Diagnostic Criteria and Nomenclature for Neurofibromatosis Type 2 and Schwannomatosis: An International Consensus Recommendation. Genet Med. 2022 Sep;24(9):1967-1977. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2022.05.007. Epub 2022 Jun 9. PMID: 35674741.

Saleh M, Dib A, Beaini S, Saad C, Faraj S, El Joueid Y, Kotob Y, Saoudi L, Emmanuel N. Neurofibromatosis Type 1 System-Based Manifestations and Treatments: A Review. Neurol Sci. 2023 Jun;44(6):1931-1947. doi: 10.1007/s10072-023-06680-5. Epub 2023 Feb 24. PMID: 36826455.

Schraepen C, Donkersloot P, Duyvendak W, Plazier M, Put E, Roosen G, Vanvolsem S, Wissels M, Bamps S. What to Know About Schwannomatosis: A Literature Review. Br J Neurosurg. 2022 Apr;36(2):171-174. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2020.1836323. Epub 2020 Dec 2. PMID: 33263426.

Shofty B, Barzilai O, Khashan M, Lidar Z, Constantini S. Spinal Manifestations of Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Childs Nerv Syst. 2020 Oct;36(10):2401-2408. doi: 10.1007/s00381-020-04754-9. Epub 2020 Jun 20. PMID: 32564155.

Solares I, Viñal D, Morales-Conejo M, Rodriguez-Salas N, Feliu J. Novel Molecular Targeted Therapies for Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 with Inoperable Plexiform Neurofibromas: A Comprehensive Review. ESMO Open. 2021 Aug;6(4):100223. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100223. Epub 2021 Aug 10. PMID: 34388689; PMCID: PMC8363824.

Tamura R. Current Understanding of Neurofibromatosis Type 1, 2, and Schwannomatosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 May 29;22(11):5850. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115850. PMID: 34072574; PMCID: PMC8198724.

Weissman A, Jakobi P, Zaidise I, Drugan A. Neurofibromatosis and Pregnancy. An update. J Reprod Med. 1993 Nov;38(11):890-6. PMID: 8277488.