Cardiovascular Health and Paralysis

The cardiovascular system of the body includes the heart (cardio) and all the blood vessels (vascular). The heart is a pump that causes blood to move throughout the entire body using blood vessels. Arteries carry blood away from the heart to supply oxygen and nutrients to every cell in the body. Blood also carries electrolytes and hormones to regulate body functions. Veins carry blood that contains waste products to the kidneys for elimination. Blood then travels back to the heart. Re-oxygenation is picked up in the lungs.

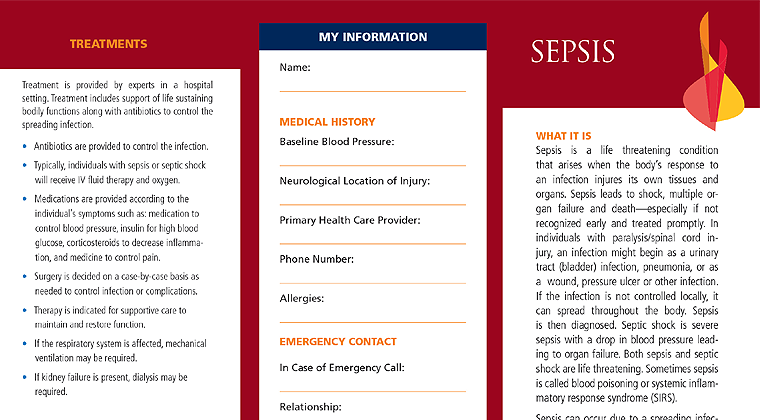

The nervous system controls cardiovascular function through the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). This is the part of the nervous system that regulates actions in the body automatically, without your consciously thinking about doing the activity. The ANS directs how fast the heart beats, the force of heart muscle contractions to push blood through your body and manages the amount of resistance in blood vessels.

The ANS consists of two coordinating systems, the sympathetic nervous system (speeds up body activity) and the parasympathetic nervous system (slows down body activity). Increases in sympathetic nerve activity speeds heart rate and the velocity and force of cardiac (heart) contractions. The parasympathetic nervous system slows heart rate and regulates blood pressure through the vagus nerve. This balance increases blood flow when needed and slows blood flow when the body is less active.

Reprinted by permission from Copyright Clearance Center: Springer Nature. Nature Review Cardiology (Neural mechanisms of atrial arrhythmias, Mark J. Shen et al), COPYRIGHT 2011

Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease

The risks of cardiovascular disease are many. Most of the risks can be controlled or affected by diet, exercise, meditation, and medication. Genetic factors cannot be altered but may be positively affected by control of health conditions and behaviors. The risks listed below are for all individuals. Paralysis can increase the risk due to secondary complications. These are complications that result due to paralysis such as development of obesity or diabetes from inactivity.

Health Conditions that Increase Heart Disease Risk

- High blood pressure

- Unhealthy cholesterol levels

- Diabetes

- Obesity

Behaviors that Increase Heart Disease Risk

- A diet high in saturated fats, trans fat, and cholesterol

- Salt use can elevate blood pressure

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Alcohol use

- Tobacco use

Genetics

- Inherited genes that affect heart disease

- Advancing age increases the risk of cardiovascular disease

- In the U.S., individuals in the ethnic groups of African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, and white people have heart disease as the leading cause of death. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and Hispanics’ leading cause of death is cancer followed by heart disease.

Learn more about risks for heart disease at this website: Know Your Risk for Heart Disease

To be effective, the cardiovascular system needs to be functioning well. This includes a well-organized nervous system for control, competent pumping by your heart and the ability to push blood through the arteries and veins. Diseases that affect the cardiovascular system include:

- Arrhythmias or abnormal heart rhythms

- Aorta disease and Marfan syndrome (an inherited disease of connective tissue)

- Congenital heart disease

- Coronary artery disease (narrowing of the arteries)

- Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- Heart attack

- Heart failure

- Heart muscle disease (cardiomyopathy)

- Heart valve disease

- High blood pressure

- Pericardial disease

- Peripheral vascular disease

- Rheumatic heart disease

- Stroke

- Vascular disease (blood vessel disease)

The Effects of Paralysis on the Cardiovascular System

Cardiovascular concerns are issues due to paralysis both from disease and trauma. Injury to the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) is the primary cause for cardiac issues after paralysis. Those with spinal cord injury or disease affecting the spine at T6 or above have an increased risk of cardiac issues due to affects to the ANS. Risks factors particular to individuals with paralysis include obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, deconditioning, and inflammation.

In paralysis from trauma, cardiovascular issues appear at the time of onset. Cardiovascular issues from disease can begin at any time in the disease process. Early issues of cardiac concerns include arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats) which can affect blood flow and clotting and bradycardia (slow heartbeat). Cardiac arrest can occur from slow to absent nerve communication. Early evolving but ongoing concerns include orthostatic hypotension (OH) which is low blood pressure especially when changing to an upright position, deep venous thromboembolism (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) or blood clots, and autonomic dysreflexia (AD) which is an inability to control blood pressure.

Over time, leading a sedentary or inactive lifestyle affects the cardiac system. One of the primary issues of inactivity is obesity. This places more challenges on the heart and vascular system to function effectively. For individuals with mobility concerns, extra weight can make transfers and movement more difficult, positioning for catheterization more challenging, bowel programs less effective and increase skin conditions and pressure injury risk. Extra weight can also lead to arthritis. When sitting, especially on the commode or shower chair, increased weight of the torso is on an unsupported rectal area which can lead to hemorrhoids or rectal prolapse. Sleep apnea and increased work of breathing from adipose (fat) tissue can challenge an individual with paralysis. Increased body mass requires more blood supply which is an extra burden on the heart increasing cholesterol levels with lower HDL (good cholesterol).

Insulin resistance and diabetes are other results of a sedentary lifestyle. Insulin resistance is when cells in the body are not able to metabolize the hormone insulin which leads to higher levels of glucose in the blood. Glucose is not able to enter body cells but is collected in the blood, stored in the liver and muscles causing significant tissue and nerve damage. Insulin resistance leads not only to weight gain but also is a precursor to type II diabetes.

Dyslipidemia or elevated levels of lipids (triglycerides, cholesterol and/or fat phospholipids) can build up leading to atherosclerosis which is a reduction in artery elasticity. It is a form of cardiovascular disease.

Later issues of paralysis that may affect cardiovascular function are effects of medication used to treat issues of spinal cord injury (stimulants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), clonidine, some antidepressants), an increase in coronary artery disease (affecting heart arteries) and peripheral vascular disease (affecting the blood vessels). An increased risk of atherosclerosis in long term spinal cord injury is due to increased weight, high cholesterol, and diabetes which can lead to metabolic syndrome. Hypertension or high blood pressure can occur which is when the force of blood through the arteries is high creating increased pressure which can also lead to heart disease. Deconditioning occurs due to lack of use of body muscles. Inflammation can occur within the body as a long-term response to health conditions.

Physical Assessments for Cardiac Risk

Body assessments can be made to determine your risk of cardiac disease. These include:

Pulse assessment by gently pressing on the radial pulse in your wrist and counting the beats for one minute is a determination of how quickly your heart is beating. You can also feel if it is strong, weak, and regular. Pulse assessment at the neck using the carotid artery should be used with caution as you can deter circulation to your brain if performed for too long or incorrectly. The wrist pulse should be assessed prior to activity, during activity and after activity. Activity to the body can be exercise or general daily care such as performing pressure releases or a bowel program.

Blood pressure is measured using a blood pressure cuff. This measures the pressure in your blood vessels, or the force of blood being pumped through your body. It also should be assessed before, during and after activity. Blood pressure will provide knowledge about your personal average as well as an indication if you are having an episode of AD. To know if AD is occurring with or without symptoms (silent AD), you will need to know your personal normal blood pressure.

Waist circumference measurement is often used as an indication of cardiovascular risk. It may not be as reliable in individuals with paralysis. Indication of risk are waist measurements in men greater than 40 inches (102 cm), in women greater than 35 inches (88 cm). These are the same measurement indicators of the entire population. They can be used as a guide however, due to lax abdominal muscles from paralysis, waist circumference may not be a good indicator for those with paralysis.

Compartment modeling is a good indication of body composition. There are three tests: 2-compartment modeling indicates body fat mass from the fat-free mass, 3-compartment modeling includes fat mass, total body water and fat-free mass, and 4-compartment modeling is fat mass, total body water, bone mineral mass and fat-free mass.

Body Mass Index is a calculation of height and weight. Calculate your body mass index here. The determining level of body mass index of equal or greater than 22kg/m2 indicates obesity in those with spinal cord injury.

EKG (electrocardiogram) is a non-invasive test performed by application of electrodes placed on your chest and leg. The electrical current of your heart is transmitted to a machine that creates a paper printout of your heart rate and rhythm.

A stress test is a procedure where the heart’s blood flow is challenged in a safe setting. People generally know this as a treadmill test. For individuals with paralysis, a medication (adenosine, dipyridamole (Persantine), or dobutamine) is given via I.V. which causes stress to the heart instead of using the treadmill. An EKG is used to assess how your heart responds.

Cardiac catheterization is an internal measure of the function of your heart. A small catheter is threaded through an artery in the groin, wrist, or elbow to assess the function of your heart’s blood vessels.

Actions to Reduce or Treat Cardiac Disease

There are behaviors and activities that can reduce your risks of heart disease. These are used to lower controllable risks. Genetic risks cannot be controlled as they are inherited. Although genetic risks cannot be changed, there may be some positive influence by controlling risk factors that can be altered.

Diet

Due to decreased movement, there is also a decrease in the energy needed or calories required to maintain the body. Many individuals with paralysis require less calories for their daily activities. However, the amount of food consumed typically remains the same due to habits established before injury or disease. Some individuals overeat for entertainment or pleasure. Others have difficulty eating enough food to maintain their body due to feeling full because of a sluggish bowel or extra energy expenditure due to tone (spasms).

To get the calories needed for you as an individual, a nutritional consult is recommended to establish the number of calories needed per day as well as a diet that is healthy for you to follow. A nutritionist or dietician can establish a program specifically for your needs. A professional with experience in the needs of individuals with spinal cord injury or paralysis from any diagnosis is helpful.

For those with cardiac issues, the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet is often recommended. It is designed to control hypertension. This may or may not be the diet for you, but it is the most common for treatment of cardiac disease in any individual without paralysis. The nutritionist may incorporate this diet altered to your specific needs. The DASH diet consists of:

- Eating vegetables, fruits, and whole grains

- Including fat-free or low-fat dairy products, fish, poultry, beans, nuts, and vegetable oils

- Limiting foods that are high in saturated fat, such as fatty meats, full-fat dairy products, and tropical oils such as coconut, palm kernel, and palm oils

- Limiting sugar-sweetened beverages and sweets.

The DASH diet meal plan can be found in many locations on the internet. A good starting place is here: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/dash-eating-plan. However, most of the diet plans for individuals with cardiac issues include consuming more calories than are needed after paralysis. The nutritional assessment will provide you with the number of calories and specific nutrients for your needs.

Caution

Some individuals will want to opt for quick fix diets and surgeries that are so heavily advertised. It is critical to remember that your body may not receive the nutrients needed in restrictive diets. With paralysis or other major health issues, your body may react differently to pills and supplements for weight loss. It may be difficult to keep up with the dietary needs and exercise required after bariatric (weight loss) surgery. In all these weight loss methods, significant injury to your body can occur. This is because your body may not receive or be able to metabolize the specific nutrients needed to maintain health with paralysis.

Medication

Medication should be taken as prescribed for complications of paralysis. Many healthcare issues may not have symptoms that you sense or see. Even though you are feeling well, medication must be taken to avoid complications of these diseases.

Dyslipidemia or high cholesterol can be triggered due to lowered levels of HDL-C (a lipoprotein that carries low cholesterol in the blood). Monitoring of cholesterol levels is key to early intervention.

Diabetes can be effectively controlled with medication, diet, and exercise. Generally, in individuals with paralysis, type II diabetes (adult onset) is diagnosed. Metformin, an oral pill, is the most frequently prescribed medication. For others, medications via weekly injections are given. Testing blood sugar by a finger prick will indicate your blood glucose (sugar). This will help you determine how well you are managing diabetes. There are some devices that are worn on the skin and watches that can indicate your blood sugar. The A1C is a blood test analyzed in a laboratory which will indicate your overall diabetes control. The goal is for A1C to be under 7.

Hypertension should be assessed and treated. Individuals with paralysis usually have lower blood pressure readings over time. Keep a close assessment of your blood pressure using a home blood pressure cuff at different points in the day and with different activities. Within a year, individuals with paralysis will typically have an average blood pressure with the systolic number (the top number) of 100 when laying and 110 when sitting. A blood pressure of 120 or 130 may be considered normal or high normal in individuals without paralysis but would be high blood pressure for those with paralysis.

Many medications are available for individuals with hypertension. You might need several attempts to find the right one for you. Blood pressure medication can affect orthostatic hypotension (OH). This can be combated by elevating your head slower, wearing compression stockings, or trying an antihypertensive medication that has less effect on OH.

Smoking

Smoking is linked to cardiac (heart) disease. Both smoking yourself as well as secondhand smoke from individuals around you have effects on your heart health. Research indicates vaping or inhaling other substances also affects your heart function.

Smoking cessation programs are available that are effective. This is essential for you and those around you. Many medical payors will financially support your efforts. Smoking is addictive. It is difficult to stop without assistance. Some individuals will stop smoking on their first attempt. Others might need several attempts, but success is possible.

Exercise

Benefits of Exercise

Exercise for all individuals has been recognized as having many benefits. Your mental well-being is affected by exercise in maintaining brain function throughout life, reduction of anxiety and depression, and improvement in sleep. Metabolism can be positively affected to maintain or reduce weight. Exercise has been associated with reducing risks of diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes type II, certain cancers, strengthening bones and muscles, improving balance, and extending life. It can combat deconditioning.

For individuals with chronic health conditions including neurological diseases and injury, exercise can stimulate nerves and muscles even if not under your own power or control. Your body requires movement. Active or passive exercise provides this stimulation to the body. The body will have a positive response, even if you cannot sense this feeling. There are many positive body responses to movement including shaking the bladder which may reduce infections and accelerate the bowel to increase peristalsis (movement). Exercise will stimulate neuroplasticity (the nervous system’s ability to reorganize), make new connections and adjustments. New nerve buds can sprout.

Routine activities of daily living such as wheelchair mobility, transfers, and pressure relief may not achieve cardiac exercise goals. Arms have smaller muscles than the major muscles of the legs. Therefore, daily activities likely will not lead to the cardiac workout you hope to achieve. An exercise program that is designed to improve health can be created.

Preparation for Exercise

When thinking about beginning an exercise program, it is strongly advised to discuss your plans with your healthcare professional. At a minimum, yearly follow up examinations should be performed. Anyone can have hidden issues lurking in their bodies that do not have symptoms. Those with chronic conditions have an increased risk. Therefore, getting medical approval to begin and maintain an exercise program is critical.

Your healthcare professional should assess you for these issues:

Cardiovascular issues including obesity (overweight) especially visceral fat which surrounds the internal organs, underweight (may indicate muscle wasting), insulin resistance (an inability to absorb glucose), dyslipidemia (elevated cholesterol) and hypertension (high blood pressure). Know your average blood pressure to assess if you have hypertension.

Autonomic Dysreflexia (AD) is a disruption in the autonomic nervous system. Exercise, especially starting or advancing an exercise program can trigger episodes of AD. https://www.ChristopherReeve.org/cards

Body temperature regulation can be affected by exercise increasing metabolism creating heat within the body. Combined with decreased sweating, too much internal heat can be triggered by exercise resulting in heat-related conditions.

Bone health to ensure your bones are strong enough to withstand exercise. Demineralization of bones is a secondary complication of spinal cord injury and paralysis.

Breathing ability to assess the capacity to exchange the added oxygen needed in exercise.

Deconditioning is the result of illness, long term bedrest, inactivity, or sedentary lifestyle. Your strength and muscles may not be at the level of pre-injury. Begin exercise slowly and build over time.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/Pulmonary embolism (PE) are blood clots that can be present in the body without symptoms. Exercise can dislodge the clots which can travel to the heart, lungs, or brain.

Fitness level currently to establish where you should begin your exercise program.

Inflammation of the internal body occurs with chronic conditions. This can lead to changes on a cellular level.

Joint flexibility and contractures can include shortening of the muscles especially at the joints. Overstretching contracted muscles can lead to muscle injury and tearing.

Muscle strength to ensure your muscles can withstand the strain of exercise.

Nutrition assessment will indicate if you require more calories, protein, or dietary supplements to assist your body and to get the maximum benefit from exercise. Follow a healthy diet including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, poultry, fish, beans, and nuts.

Pressure injury or open areas of skin on the body can be affected by added stress and pressure to the area.

Spine stability should be assessed to ensure movement will not further affect your body.

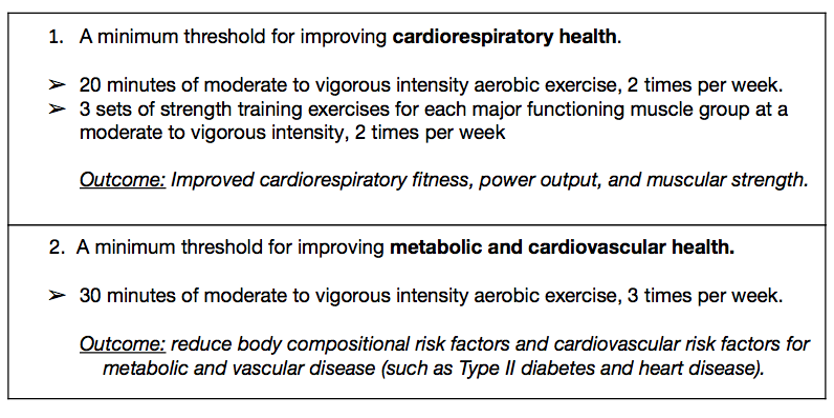

Exercise Guidelines for Individuals with Chronic Conditions

Exercise for adults with chronic conditions and those with spinal cord injury each have published guidelines. The guidelines to follow should be selected by you and a health professional to meet your individual needs. When first beginning an exercise program, you may not be able to perform at the levels presented in either of these guidelines. The best course of action is to begin slowly and increase over time. A healthcare professional will be able to establish an exercise program that is right for you.

Exercise Guidelines for Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury

Martin Ginis, K.A., van der Scheer, J.W., Latimer-Cheung, A.E. et al. Evidence-based scientific exercise guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury: an update and a new guideline. Spinal Cord 56, 308–321 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-017-0017-3. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41393-017-0017-3….

Exercise Guidelines for Individuals with Chronic Health Conditions and Adults with Disabilities.

Key Guidelines for Adults with Chronic Health Conditions and Adults with Disabilities

From: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

Adults with chronic conditions or disabilities, who are able, should do at least 150 minutes a week (2 hours and 30 minutes) to 300 minutes (5 hours) a week of moderate-intensity, or 75 minutes (1 hour and 15 minutes) to 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) a week of vigorous- intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate and vigorous- intensity aerobic activity. Preferably, aerobic activity should be spread throughout the week.

Adults with chronic conditions or disabilities, who are able, should also do muscle strengthening activities of moderate or greater intensity and that involve all major muscle groups on two or more days a week, as these activities provide additional health benefits.

When adults with chronic conditions or disabilities are not able to meet the above key guidelines, they should engage in regular physical activity according to their abilities and should avoid inactivity.

Adults with chronic conditions should be under the care of a health care provider. People with chronic conditions can consult a health care professional or physical activity specialist about the types and amounts of activity appropriate for their abilities and chronic conditions.

Note that the parameters for heart rate considered typical in exercise programs is not mentioned in either guideline. Individuals with paralysis may not reach the heart rate parameters, however benefits from exercise are still gained by increasing physical conditioning. Heart rate should still be monitored by assessing your pulse and blood pressure. Both are to ensure the body is not overstressed leading to complications. You may not feel the aches and pains of exercise, but your body will still react to discomfort. This might be indicated by AD episodes or cardiac pain that may appear without symptoms or as referred pain to the shoulder or jaw.

Begin your exercise program slowly and gently. Start at 10 minutes/day or less. Set a schedule to increase your time and exercise intensity at a comfortable pace. Listen to your body clues to establish a pace that is right for you.

Check your skin frequently. As your body is moving or being moved, body weight will shift. Shoes, pants, waist bands, and shirts that did not rub might now create pressure areas. Equipment may create pressure areas, friction, or a shearing injury.

Monitor for autonomic dysreflexia (AD), increased spasticity, and incontinence. Continue with pressure relief actions and use of pressure dispersing equipment. Pressure cushioning on exercise equipment may not be at the level of pressure dispersion that you require. You may need to use your pressure dispersion cushions with exercise equipment.

Sites for examples of exercise:

Rehabilitation Professionals for Cardiac Health

Physiatrist-is a physician who specializes in rehabilitation. This individual will assist you with your health assessments. They will direct your wellness program with diet, exercise, and overall health conditions.

Primary care physician or nurse practitioner–will assess your general health diagnosing and providing treatments for diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and other health issues as needed.

Cardiologist—is a physician who specializes in the care of the heart and vascular system. They will provide assessments and treatments based on your cardiac needs.

Rehabilitation registered nurse--can assist with issues of diet, medication administration and side effects, education about identification and treatment of autonomic dysreflexia (AD) and skin protection.

Physical therapist or exercise physiologist–will help establish an exercise plan that is right for your specific needs. They can advance the plan as needed.

Dietician–will create a calorie and nutrition plan for your needs to ensure you have the right foods and diet.

Cardiac Research

Inflammation is known to be a trigger for cardiac issues, but the physiology is not clearly understood in general and especially in those with spinal cord injury or paralysis from other issues. Scientists are studying this phenomenon on a molecular and whole-body scale. Both cardiac and neurological issues have been closely related to inflammation and its effects. These areas are under intense scrutiny but require further investigation.

Some factors that affect cardiac health can be modified with diet, exercise, and smoking cessation. Risk factors for cardiac disease are being studied with individuals with and without spinal cord diseases and paralysis. Genetic factors are being studied to see if modification can be made. Unlocking the complex physiological mechanisms and methods to improve cardiac health is being studied from multiple directions.

In the study of individuals with spinal cord injury, much attention has recently focused on the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The effects of specific functions of the ANS such as temperature regulation, autonomic dysreflexia (AD), and orthostatic hypotension (OH) have historically been examined separately and research in these areas continues today. More recently an increased effort of the study of functions of the ANS as a whole are being research. The goal is to look at the source of issues of the ANS to create treatments for the total system rather than separate complications.

Facts and Figures

In the United States, 47% of all individuals have at least one of three key risk factors for heart disease: high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking.

The National SCI Database indicates death from cardiac disease with spinal cord injury is declining. However, metabolic, nutritional, and endocrine diseases are slowly increasing.

Physiological effects on the cardiac system after spinal cord injury include effects to the function of the autonomic nervous system especially in those with injury above T6, smaller left ventricle heart volumes and mass, and alterations in blood pressure function.

Resources

If you are looking for more information about cardiovascular health or have a specific question, our Information Specialists are available business weekdays, Monday through Friday, toll-free at 800-539-7309 from 9:00 am to 8:00 pm ET.

Additionally, the Reeve Foundation maintains fact sheets with additional resources from trusted Reeve Foundation sources. Check out our repository of fact sheets on hundreds of topics ranging from state resources to secondary complications of paralysis.

We encourage you to reach out to organizations, including associations which features news, research support, and resources, support groups, clinics, and specialty hospitals.

Clinical Guidelines

References

Bauman WA, Spungen AM. Coronary heart disease in individuals with spinal cord injury: assessment of risk factors. Spinal Cord. 2008 Jul;46(7):466-76. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102161. Epub 2008 Jan 8. PMID: 18180789.

Biering-Sørensen F, Biering-Sørensen T, Liu N, Malmqvist L, Wecht JM, Krassioukov A. Alterations in cardiac autonomic control in spinal cord injury. Auton Neurosci. 2018 Jan;209:4-18. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2017.02.004. Epub 2017 Feb 15. PMID: 28228335.

Brazg G, Fahey M, Holleran CL, Connolly M, Woodward J, Hennessy PW, Schmit BD, Hornby TG. Effects of training intensity on locomotor performance in individuals with chronic spinal cord injury: A randomized crossover study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2017 Oct-Nov;31(10-11):944-954. doi: 10.1177/1545968317731538. Epub 2017 Oct 30. PMID: 29081250; PMCID: PMC5729047.

Collins HL, Rodenbaugh DW, DiCarlo SE. Spinal cord injury alters cardiac electrophysiology and increases the susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias. Prog Brain Res. 2006;152:275-88. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)52018-1. PMID: 16198707.

DeVeau KM, Martin EK, King NT, Shum-Siu A, Keller BB, West CR, Magnuson DSK. Challenging cardiac function post-spinal cord injury with dobutamine. Auton Neurosci. 2018 Jan;209:19-24. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2016.12.005. Epub 2016 Dec 23. PMID: 28065654; PMCID: PMC5481490.

Ditterline BL, Wade S, Ugiliweneza B, Singam NSV, Harkema SJ, Stoddard MF, Hirsch GA. Systolic and diastolic function in chronic spinal cord injury. PLoS One. 2020 Jul 27;15(7):e0236490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236490. PMID: 32716921; PMCID: PMC7384657.

Fryar CD, Chen T, Li X. Prevalence of uncontrolled risk factors for cardiovascular disease: United States, 1999–2010. NCHS data brief, no 103. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2012. https://www.christopherreeve.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/db103.pdf

Hagen EM, Rekand T, Grønning M, Faerestrand S. Cardiovascular complications of spinal cord injury. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2012 132:1115-20. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.11.0551 https://tidsskriftet.no/en/2012/05/cardiovascular-complications-spinal-cord-injury#article

Jacobs PL, Nash MS. Exercise recommendations for individuals with spinal cord injury. Sports Med. 2004;34(11):727-51. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434110-00003. PMID: 15456347.

Kim DI, Tan CO. Alterations in autonomic cerebrovascular control after spinal cord injury. Auton Neurosci. 2018 Jan;209:43-50. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2017.04.001. Epub 2017 Apr 4. PMID: 28416148; PMCID: PMC6432623.

Martin Ginis, KA, van der Scheer, JW, Latimer-Cheung, AE et al. Evidence-based scientific exercise guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury: an update and a new guideline. Spinal Cord 56, 308–321 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-017-0017-3. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41393-017-0017-3.pdf

Maher JL, McMillan DW, Nash MS. Exercise and health-related risks of physical deconditioning after spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2017 Summer;23(3):175-187. doi: 10.1310/sci2303-175. PMID: 29339894; PMCID: PMC5562026.

Mneimneh F, Moussalem C, Ghaddar N, Aboughali K, Omeis I. Influence of cervical spinal cord injury on thermoregulatory and cardiovascular responses in the human body: Literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2019 Nov;69:7-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2019.08.022. Epub 2019 Aug 22. PMID: 31447370.

Myers J, Lee M, Kiratli J. Cardiovascular disease in spinal cord injury: an overview of prevalence, risk, evaluation, and management. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007 Feb;86(2):142-52. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31802f0247. PMID: 17251696.

Orr MB, Gensel JC. Spinal cord injury scarring and inflammation: Therapies targeting glial and inflammatory responses. Neurotherapeutics. 2018 Jul;15(3):541-553. doi: 10.1007/s13311-018-0631-6. PMID: 29717413; PMCID: PMC6095779.

Prévinaire JG, Mathias CJ, El Masri W, Soler JM, Leclercq V, Denys P. The isolated sympathetic spinal cord: Cardiovascular and sudomotor assessment in spinal cord injury patients: A literature survey. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010 Oct;53(8):520-32. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2010.06.006. Epub 2010 Aug 13. PMID: 20797928.

Squair JW, DeVeau KM, Harman KA, Poormasjedi-Meibod MS, Hayes B, Liu J, Magnuson DSK, Krassioukov AV, West CR. Spinal cord injury causes systolic dysfunction and cardiomyocyte atrophy. J Neurotrauma. 2018 Feb 1;35(3):424-434. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.4984. Epub 2017 Oct 13. PMID: 28599602.

Tweedy SM, Beckman EM, Geraghty TJ, Theisen D, Perret C, Harvey LA, Vanlandewijck YC. Exercise and sports science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise and spinal cord injury. J Sci Med Sport. 2017 Feb;20(2):108-115. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2016.02.001. Epub 2016 Mar 9. PMID: 27185457.

Thompson WG, Namey TC. Cardiovascular complications of inactivity. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1990 Nov;16(4):803-13. PMID: 2087577.

van der Scheer JW, Martin Ginis KA, Ditor DS, Goosey-Tolfrey VL, Hicks AL, West CR, Wolfe DL. Effects of exercise on fitness and health of adults with spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Neurology Aug 2017, 89 (7) 736-745; DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004224.

Williams AM, Gee CM, Voss C, West CR. Cardiac consequences of spinal cord injury: systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2019 Feb;105(3):217-225. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313585. Epub 2018 Sep 27. PMID: 30262456.

Wouda MF, Lundgaard E, Becker F, Strøm V. Effects of moderate- and high-intensity aerobic training program in ambulatory subjects with incomplete spinal cord injury–a randomized controlled trial. Spinal Cord. 2018 Oct;56(10):955-963. doi: 10.1038/s41393-018-0140-9. Epub 2018 May 23. PMID: 29795172.