Syringomyelia and Tethered Cord

There are health conditions that affect the spinal cord. Two of these conditions are syringomyelia and tethered cord syndrome, which can develop separately or together. The causes of each are quite different or one may cause the other to develop.

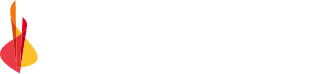

Syringomyelia is a cyst (fluid-filled pocket) that develops within the spinal cord. The cyst fills with cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) which can alter the CSF flow needed to cradle the brain and spinal cord. This particular cyst is called a syrinx. The syrinx generally forms within the center of the spinal cord with a tract that connects to the area of cerebral spinal fluid.

In syringomyelia, the cyst (syrinx) fills with cerebral spinal fluid which cannot be accommodated in the space of the spinal cord. The extra fluid within the spinal cord presses against spinal cord nerve tissue that is confined in the rigid vertebral bones thereby compromising spinal cord function. This leads to compression and damage to the nerves within the spinal cord causing the inability of messages to be passed back and forth between the brain and the body. The syrinx may be present continuously resulting in decreased function or may intermittently fill and drain which makes symptoms fluctuate.

There are several reasons why syringomyelia may develop. The most common cause in adults and children is Chiari I and II malformation which is a herniation (protrusion) of the lower brain out of the opening of the back base of the skull where the brain connects to the spinal cord. Syringomyelia can occur in children with tethered cord or as a result of some types of spina bifida. It can also be developed later, even years, after spinal cord injury as a post-injury complication. Other causes of syringomyelia are spinal cord tumors, and spinal cord inflammation such as meningitis and arachnoiditis (both protective membranes of the spinal cord).

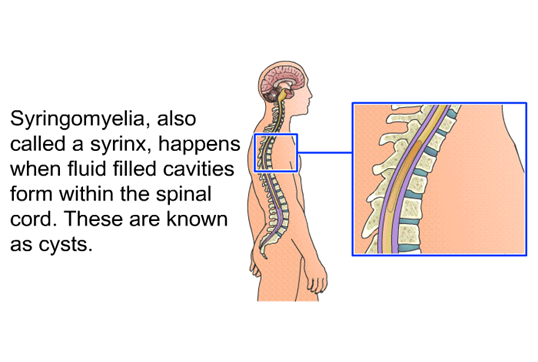

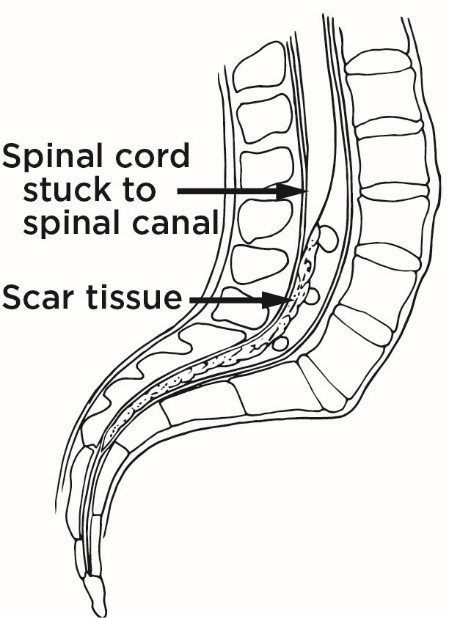

Tethered Cord Syndrome is a condition of the spinal cord, most often in children, when the somewhat elastic spinal cord becomes attached to non-elastic tissue such as the lining (dura) that contains it, connects with scar tissue, attaches to a bone spur (spicule), or tumor. The spinal cord becomes immobilized within the vertebrae instead of pleasantly floating in the cerebral spinal fluid. It becomes tethered or locked onto another part of the anatomy that is not as flexible, so the natural movement of the spinal cord is compromised. The nerves of the spinal cord can be overstretched which affects function especially as a child grows.

Tethered cord syndrome is typically found in children with health care conditions such as spina bifida (myelomeningocele and lipomyelomeningocele), a history of spine trauma or spine surgery, spinal tumor, thickened filament near the tailbone, lipoma (fat growth), diastematomyelia (split cord), dermal sinus tract (a congenital malformation). There are some rare cases where it is not diagnosed until adulthood, usually due to symptoms of decreased motor and sensory function, and loss of bladder and bowel function.

In some children with tethered cord syndrome, other anatomical anomalies occur such as neurologic, cardiac, and urinary issues. Some are accompanied by a combination of issues. When tethered cord is diagnosed, assessments for these other companion issues will be made.

Untethering (repair) of a tethered cord is necessary to avoid the development of a syrinx (syringomyelia), nerve damage, and loss of function.

Syringomyelia and Tethered Cord Syndrome are both stand-alone conditions. They do not necessarily appear together. However, in some cases, the syrinx of syringomyelia can develop due to an unrepaired tethered cord. It is thought that if the spinal cord becomes tethered, the pull on the cord can create a cyst (syrinx) higher within the spinal cord where cerebrospinal fluid collects. A combination of tethered cord and syrinx occurs mostly in the lower third of the spinal cord but has less often been found higher in the thoracic and cervical levels.

Symptoms

Top image: Normal — Spinal cord floats freely in spinal canal. Bottom image: Tethered — Spinal cord stuck (tethered) to spinal cord.

Symptoms of syringomyelia and tethered cord syndrome are complex as the variability in the location of the syrinx and tethering affects the level where they occur. Syringomyelia may have symptoms that come and go if the syrinx is able to drain and refill. Symptoms are generally progressive. Tethered cord syndrome symptoms are typically continuously present.

Syringomyelia and tethered cord syndrome symptoms are similar. Some individuals have no symptoms of syringomyelia or tethered cord. Individuals may have some of these symptoms, or many symptoms.

The location of the syrinx in syringomyelia results in decreased function of the body controlled by that part of the spinal cord. Syringomyelia symptoms include:

- Slow onset (rarely fast onset)

- Pain in the body where sensation is present including tingling, burning, pins and needles, and numbness, or if there is an issue with sensation, referred pain to the jaw may be felt.

- Headaches

- Decreased sensitivity to hot or cold and pain

- Muscle weakness and wasting

- Increased loss of sensory perception (but usually not touch)

- Loss of reflexes

- Increased spasticity

- Ataxia (uncoordinated motor movement)

- Paralysis or an increase in paralysis

- Fasciculations (involuntary muscle ‘twitches’)

- Scoliosis, more often in children

- Degeneration of joints (first appears as swelling and redness in the joint area, followed by dysfunction)

- Effects of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) the part of the nervous system that controls functions automatically such as excessive sweating and fluctuating blood pressure.

- Loss of bowel and bladder control, bladder infections

- Horner’s syndrome (nerve damage to one side of the face and eye, droopy eyelid, decreased pupil size, and decreased sweating on the same side).

- If Chiari malformation is present, hydrocephalus (accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain).

- Those who have a spinal cord injury may notice the level of their injury is rising or they are slowly losing function. This is not usual. Once a spinal cord injury is determined, it does not rise although the level of injury may lower with improvement.

Tethered cord syndrome symptoms may include those listed above and:

- Diagnosis of spina bifida

- In children with a tethered cord, there may be changes in the shape of the legs.

- Occasionally, anal/rectal malformations may be present in children. These are corrected shortly after birth.

- Individuals with an unknown tethered cord may have a dimple, birthmark, tuft of hair, or area of fat at the lower spinal cord.

Diagnosis

To diagnose syringomyelia, tethered cord syndrome, or both, the first step is to have a physical and neurological physical examination. The physical examination is done to assess an individual’s general state of health which includes past medical history, current concerns, and physical assessment. The neurological physical examination is an assessment of mental status, the cranial nerves, the status of the motor system, sensory system, reflexes, coordination, balance, and gait. Any changes should be noted to help identify the areas affected in the body.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the main assessment of the spinal cord to look for the location of syringomyelia, tethered cord syndrome, or both. This test can distinguish between a syrinx of syringomyelia or other space-occupying issues in the spinal cord such as tumors or other neurological diseases with similar symptoms including arteriovenous malformation (AVM), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis (MS), central pontine myelinolysis, spinal muscular atrophy, diabetic neuropathy, chronic demyelinating polyneuropathy, and ankylosing spondylitis. In tethered cord, the MRI will assist with finding the precise location of the tethering as well as the thickness of the attachment. A three-dimensional MRI imaging process may be used to define the parameters of the spinal cord if surgery is planned.

Syringomyelia and tethered cord syndrome diagnosis may also involve a CT scan (computer tomography), ultrasound, and endoscopy to gain more information about the location, details of involvement, and structure of the spinal cord.

A myelogram is an X-ray with contrast material injected into the sac surrounding the spinal cord. This can help in providing information about the effects of the tethered cord.

EMG (electromyography) and NCS (nerve conduction studies) may be completed to assess changes in muscle and nerve function.

During surgery, specialized neuromonitoring systems are used to ensure the safety and functionality of the spinal cord during the operation.

Treatment

Syringomyelia is often diagnosed incidentally when an MRI is completed for other reasons. In this case, when no symptoms are present, yearly observation through a neurological examination or MRI may be used for monitoring, but no treatment is needed.

Progressing symptoms of syringomyelia, pain, or decreasing functional ability are indications that spinal cord surgery may be needed to reduce damage to the spinal cord, decrease pressure, and restore the usual flow of cerebral spinal fluid. Several approaches may be taken depending on the cause of the syrinx. If the source is Chiari malformation, reduction of pressure may resolve the issue by partially removing or enlarging the base of the skull where the spinal cord is attached to the brain. Removal of an obstruction such as a tumor or bone spur may drain the syrinx. In some cases, such as spinal cord injury, the syrinx may be drained with a shunt placed into the syrinx with emptying into the abdomen, to keep the drainage flowing out of the syrinx. Repair of a tethered cord may restore cerebral spinal fluid flow, thereby reducing the syrinx.

Outcomes can vary after surgery for syringomyelia. The syrinx may resolve, may need additional treatment, or may remain. Follow-up care to assess the syrinx should be provided.

Repair of the tethered cord is also spinal surgery. The procedure is referred to as ‘untethering’. This is a necessary surgery to avoid the development of syringomyelia or other issues that can damage the spinal cord. An incision is made through the skin, a part of the vertebrae (spine bone) is removed, and the spinal cord is gently released from the area of attachment. As most tethered cord procedures are in children with spina bifida, the original scar area for closure is used for the untethering procedure. Typically, this surgery is performed one time. Rarely, during a child’s growth, the cord may re-tether which requires an additional untethering.

The Rehabilitation Health Care Team

A physiatrist is a physician who specializes in improving health and function while monitoring medical needs. Specialists are for pediatrics and adults. This individual will serve as a team leader to diagnose and direct you or your child’s care needs.

A Neurosurgeon is a specialist in surgery of the brain and/or spinal cord. They will continue to monitor you or your child’s condition to ensure progress and avoid complications from the surgical procedure.

The Rehabilitation Registered Nurse is a registered nurse who will provide care, direct home care, and educate the individual and family about providing for the needs to ensure improvement and safety. This person will ensure treatments and therapy information is incorporated into daily life. These are specialists, particularly in bowel, bladder, and skin care. Monitoring of medications is also overseen.

A Physical Therapist will provide therapeutic treatment to encourage function, proper positioning, and safety. This individual will work with gross motor movement. They will provide input to obtain the best mobility devices for home and community use.

An Occupational Therapist provides education and treatment for fine motor skills and activities of daily living. They will assist with ensuring abilities for self-care in all settings such as home, work, and school. They will provide input to equipment that will aid in these areas.

A Childlife Therapist works with children to help with distraction during procedures and tests as well as with adaption to lifestyle needs.

Research

Syringomyelia and tethered cord syndrome are being studied separately as well as together. Focus has included looking at common causes such as Chiari I and II malformations and spina bifida among others to assess how these issues lead to effects on and in the spinal cord. Identification of genetic factors is being sought to look for connections to birth defects and predispositions leading to both conditions.

Diagnostic information has been studied with advancements in tools used to detect syringomyelia and tethered cord. The development of 3D MRI imaging has greatly improved surgical intervention in being able to detect the exact location of both issues as well as preparing the surgeon for the best route of correction. These studies continue.

Rehabilitation techniques from a variety of disciplines participate in research and treatment plans. Specific information from neurology, neurosurgery, urology, gastrointestinal, and many other specialties aid in the development of treatments for the best outcomes.

Facts and Figures

Syringomyelia occurs in one out of every 100,000 individuals.

Syringomyelia occurs more in men than women.

Tethered cord occurs in 0.25 of every 1,000 births.

Tethered cord occurs in the same numbers in males and females.

Resources

If you are looking for more information about syringomyelia or tethered cord or have a specific question, our Information Specialists are available business weekdays, Monday through Friday, toll-free at 800-539-7309.

Check out our repository of fact sheets on hundreds of topics ranging from state resources to secondary complications of paralysis.

We encourage you to also reach out to support groups and organizations for individuals and families, including:

American Syringomyelia & Chiari Alliance Project

Further Reading:

National Organization for Rare Disorders:

References

Bonfield CM, Levi AD, Arnold PM, Okonkwo DO. Surgical Management of Post-Traumatic Syringomyelia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010 Oct 1;35(21 Suppl):S245-58. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f32e9c. PMID: 20881468.

Ciaramitaro P, Massimi L, Bertuccio A, Solari A, Farinotti M, Peretta P, Saletti V, Chiapparini L, Barbanera A, Garbossa D, Bolognese P, Brodbelt A, Celada C, Cocito D, Curone M, Devigili G, Erbetta A, Ferraris M, Furlanetto M, Gilanton M, Jallo G, Karadjova M, Klekamp J, Massaro F, Morar S, Parker F, Perrini P, Poca MA, Sahuquillo J, Stoodley M, Talamonti G, Triulzi F, Valentini MC, Visocchi M, Valentini L; International Experts Jury of the Chiari Syringomyelia Consensus Conference, Milan, November 11-13, 2019. Diagnosis and Treatment of Chiari Malformation and Syringomyelia in Adults: International Consensus Document. Neurol Sci. 2022 Feb;43(2):1327-1342. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05347-3. Epub 2021 Jun 15. Erratum in: Neurol Sci. 2021 Nov 17;: PMID: 34129128.

Flint G. Syringomyelia: Diagnosis and Management. Pract Neurol. 2021 Oct;21(5):403-411. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2021-002994. Epub 2021 Aug 25. PMID: 34433683.

Garvey GP, Wasade VS, Murphy KE, Balki M. Anesthetic and Obstetric Management of Syringomyelia During Labor and Delivery: A Case Series and Systematic Review. Anesth Analg. 2017 Sep;125(3):913-924. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001987. PMID: 28598915.

Giner J, Pérez López C, Hernández B, Gómez de la Riva Á, Isla A, Roda JM. Update on the Pathophysiology and Management of Syringomyelia Unrelated to Chiari Malformation. Neurologia (Engl Ed). 2019 Jun;34(5):318-325. English, Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2016.09.010. Epub 2016 Dec 9. PMID: 27939111.

Kuntz C 4th, Park TS. Tethered Cord. Introduction. Neurosurg Focus. 2010 Jul;29(1):1p preceeding E1. doi: 10.3171/2010.7.FOCUS.Intro. PMID: 20594008.

Kurzbuch AR, Magdum S. Iatrogenic Syringomyelia Postcranial Surgery in Pediatric Patients: Systematic Review and Illustrative Case. Childs Nerv Syst. 2021 Sep;37(9):2879-2890. doi: 10.1007/s00381-021-05268-8. Epub 2021 Jun 22. PMID: 34156512.

Lew SM, Kothbauer KF. Tethered Cord Syndrome: An Updated Review. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2007;43(3):236-48. doi: 10.1159/000098836. PMID: 17409793.

Li Y, Green B. Syringomyelia in Patient with Concurrent Posttraumatic Hydrocephalus and Tethered Spinal Cord: Implications for Surgical Management. World Neurosurg. 2020 Jun;138:163-168. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.02.179. Epub 2020 Mar 7. PMID: 32156596.

Li YD, Therasse C, Kesavabhotla K, Lamano JB, Ganju A. Radiographic Assessment of Surgical Treatment of Post-Traumatic Syringomyelia. J Spinal Cord Med. 2021 Nov;44(6):861-869. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2020.1743086. Epub 2020 Mar 30. PMID: 32223591; PMCID: PMC8725754.

Menezes AH, Dlouhy BJ. Congenital Cervical Tethered Spinal Cord in Adults: Recognition, Surgical Technique, and Literature Review. World Neurosurg. 2021 Feb;146:46-52. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.10.107. Epub 2020 Oct 24. PMID: 33229310.

Sáez-Alegre M, Pérez López C, Giner García J, Junnior Palpán Flores A, García Feijoo P, Vivancos Sánchez C, Isla Guerrero A. Epidural Lipomatosis and Syringomyelia in Adulthood: Case Report and Literature Review. World Neurosurg. 2019 Sep;129:341-344. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.06.075. Epub 2019 Jun 20. PMID: 31228704.

Scivoletto G, Masciullo M, Pichiorri F, Molinari M. Silent Post-Traumatic Syringomyelia and Syringobulbia. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2020 Mar 13;6(1):15. doi: 10.1038/s41394-020-0264-y. PMID: 32170091; PMCID: PMC7070058.

Tsitouras V, Sgouros S. Syringomyelia and Tethered Cord in Children. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013 Sep;29(9):1625-34. doi: 10.1007/s00381-013-2180-y. Epub 2013 Sep 7. PMID: 24013332.

Tu A, Steinbok P. Occult Tethered Cord Syndrome: A Review. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013 Sep;29(9):1635-40. doi: 10.1007/s00381-013-2129-1. Epub 2013 Sep 7. PMID: 24013333.

Wichmann TO, Pedersen M, Ringgaard S, Rasmussen MM. [Cerebrospinal Fluid Flow dynamics and the Potential of Phase-Contrast MRI in Syringomyelia]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2020 May 5;182(22):V12190730. Danish. PMID: 32515330.

Vandertop WP. Syringomyelia. Neuropediatrics. 2014 Feb;45(1):3-9. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1361921. Epub 2013 Nov 22. PMID: 24272770.